You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

making slowmatch....

- Thread starter Jim Walls

- Start date

Help Support Muzzleloading Forum:

This site may earn a commission from merchant affiliate

links, including eBay, Amazon, and others.

RAEDWALD

40 Cal.

What role would the lead acetate play? I would like to think it would either slow the burning rate and/or keep the ember from extinguishing.Canute said:Sometimes they put in lead acetate, but I'm not promoting that.

- Joined

- May 24, 2005

- Messages

- 5,522

- Reaction score

- 5,365

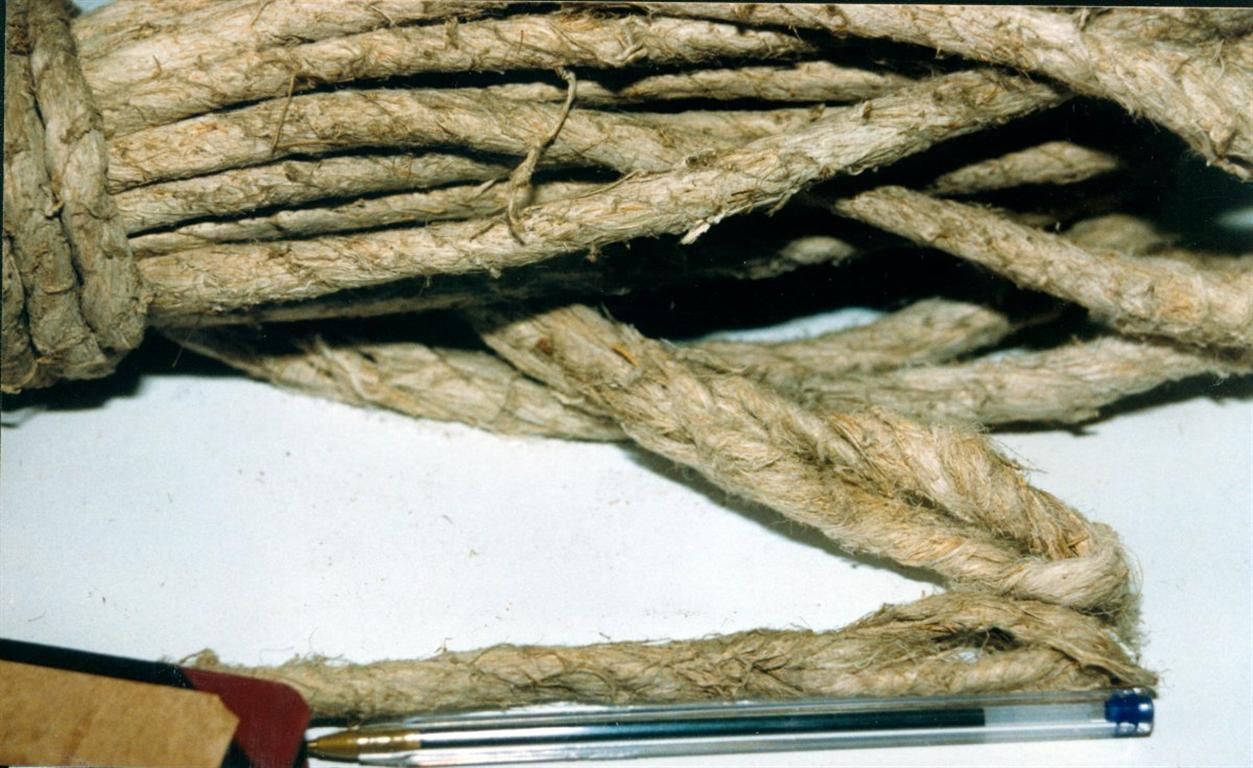

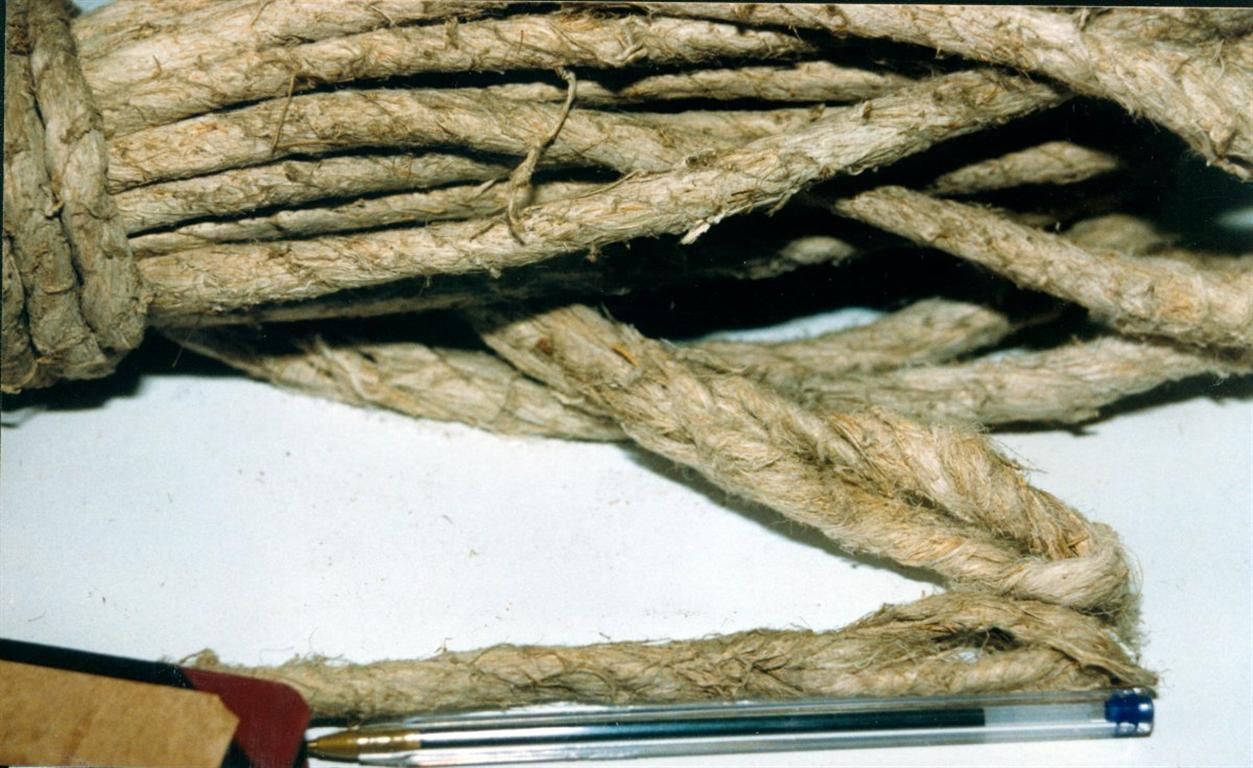

Hello all. Interesting Thread. I thought this might be an opportune time to post some photos of original match cord. Thought you guys might enjoy this.

To follow this Post, I'll submit the Author's thoughts on match cord. Interesting reading and based on existing samples from his own collection as well as others. Hope you enjoy. Rick. :thumbsup:

To follow this Post, I'll submit the Author's thoughts on match cord. Interesting reading and based on existing samples from his own collection as well as others. Hope you enjoy. Rick. :thumbsup:

- Joined

- May 24, 2005

- Messages

- 5,522

- Reaction score

- 5,365

And here is his text on the subject of match cord:

To my knowledge, nobody has cared to do close research in this topic so far.

Matchcord (Luntenstrick), also called slow match or fuse, must have been used for igniting firearms from almost the very beginning. In the earliest two pictorial representations of a gun, the Christ Church and the Holkham manuscripts by Walter de Milemete of 1326/7 (top four attachments) we cannot clearly discern what substance is actually used to ignite the gun; at least in the Christ Church ms it seems to be a somewhat longer and thicker substance much resembling a piece of match clamped in a linstock:

Anyway, matchcord seems to have come into use in the course of the 14th century. For small guns, it is recorded to have been employed until the military end of the matchlock era, which was ca. the 1730's. At that time we find the latest records and drill instructions including service employment of matchlock muskets.

Big pieces, i.e. pieces of artillery/cannon, had of course to be lit by either igniting irons (ca. 14th to 18th c.) or linstocks holding match from the 14th c. until the end of the muzzle-loading era, the mid-19th century.

Slow match basically consisted of three main strands of fibrous hemp including a considerable amount of porous cortex, twisted and soaked in saltpeter/nitrate (Salpeter/Bleizucker). As this chemical solution is volatile it can usuallly no longer be proven in existing pieces of matchcord. However, according to experiments by the author, unsoaked hemp will also smolder constantly to an extent where it can be stopped safely only be either chopping off the glowing end or dipping it into water.

From all we know, matchcord, just like saltpeter (animal urine), was produced by the rural population and purchased by the armories measured by weight. Of course, the dimensions measured up to literally tons. They were handed out to the troops in both larger and smaller bundles.

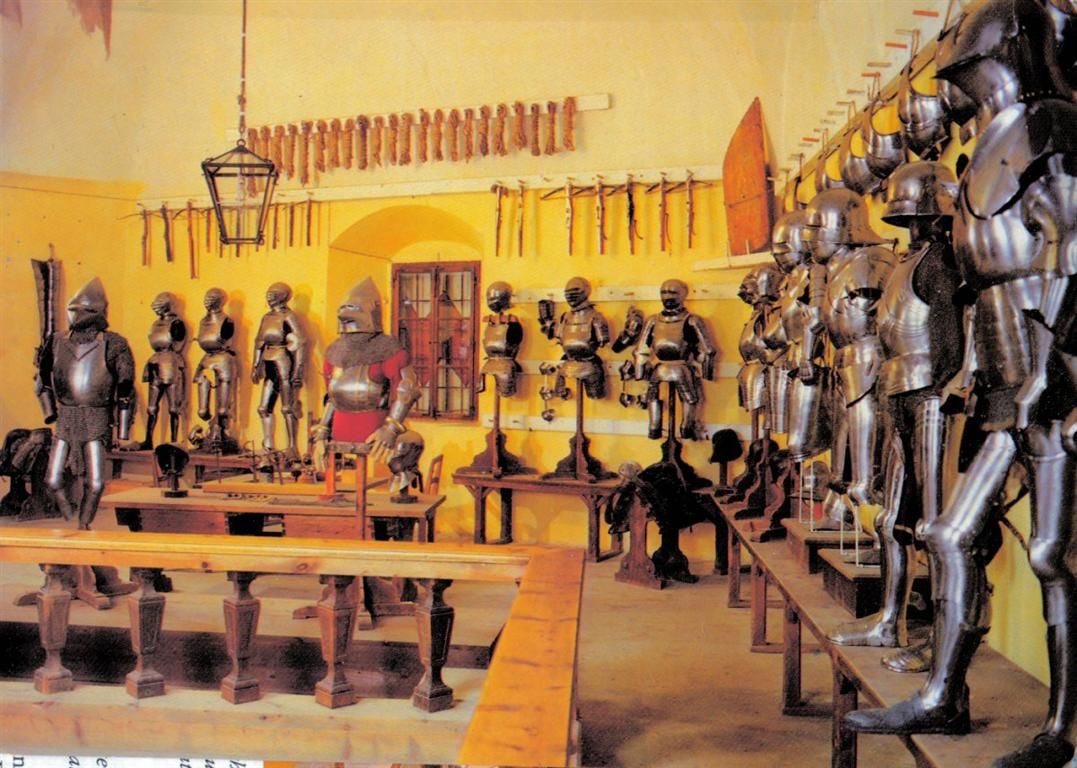

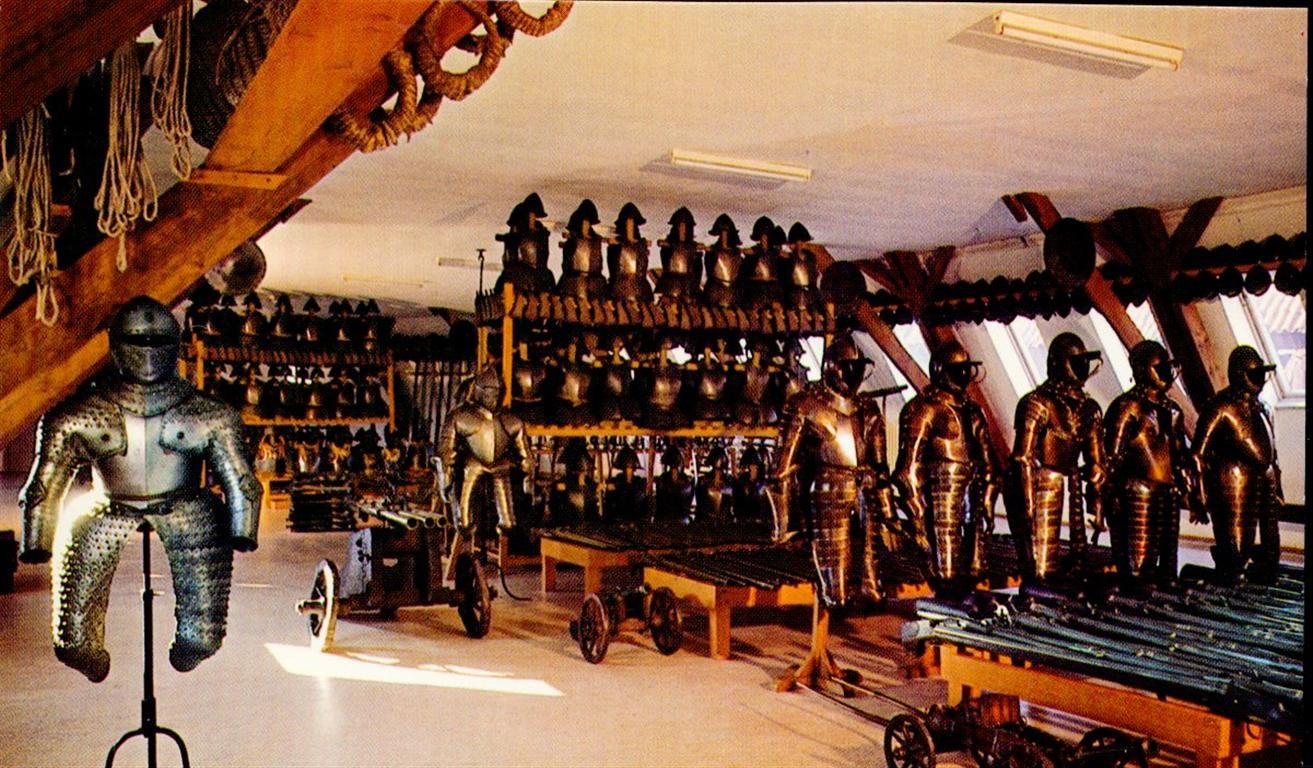

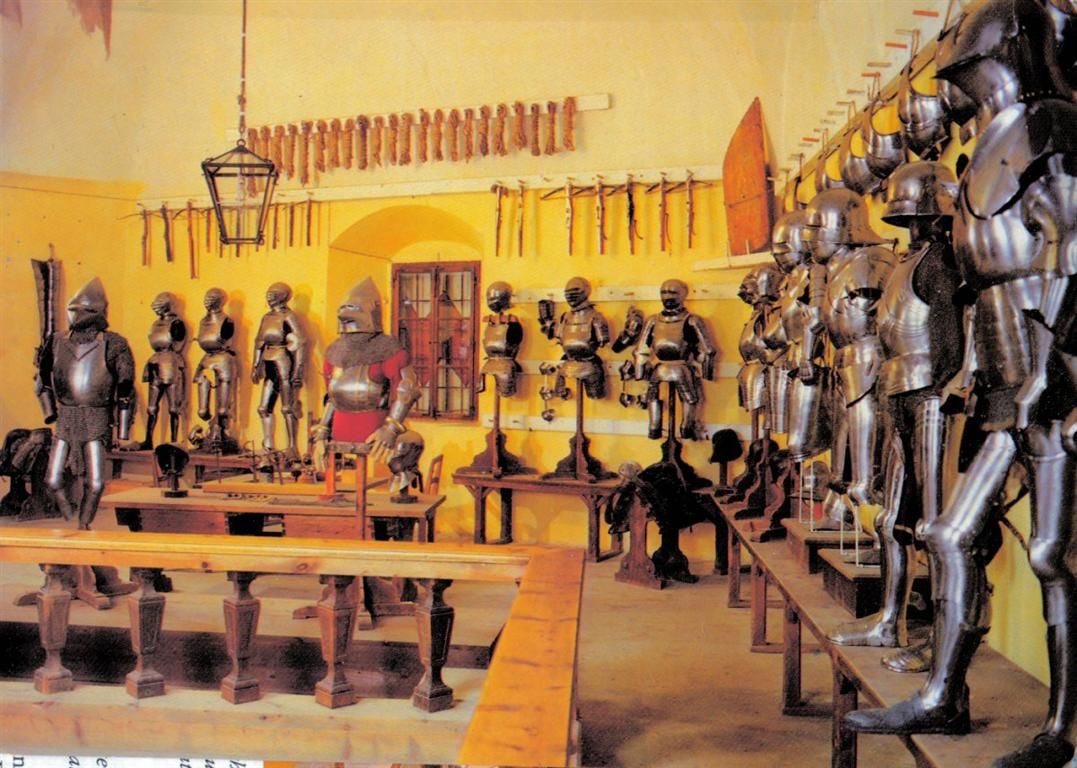

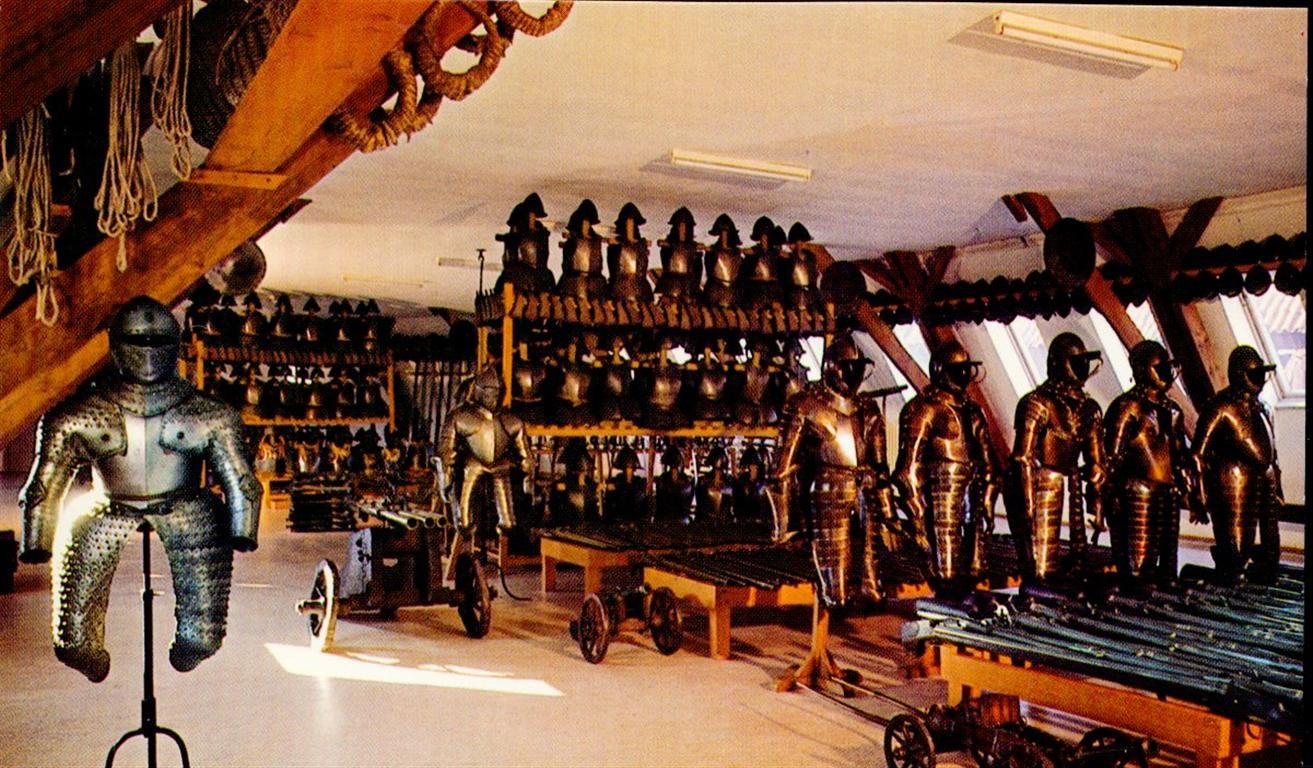

Surviving large bundles today are extremely few, known only in the armories in both Churburg, Sluderno/South Tyrol, and the Fortress Armory of Coburg/Franconia. A great number of them is known to have been kept in the fortress of Hohenwerfen near Salzburg/Austria but was sold together with the complete contents at auction in New York in 1927.

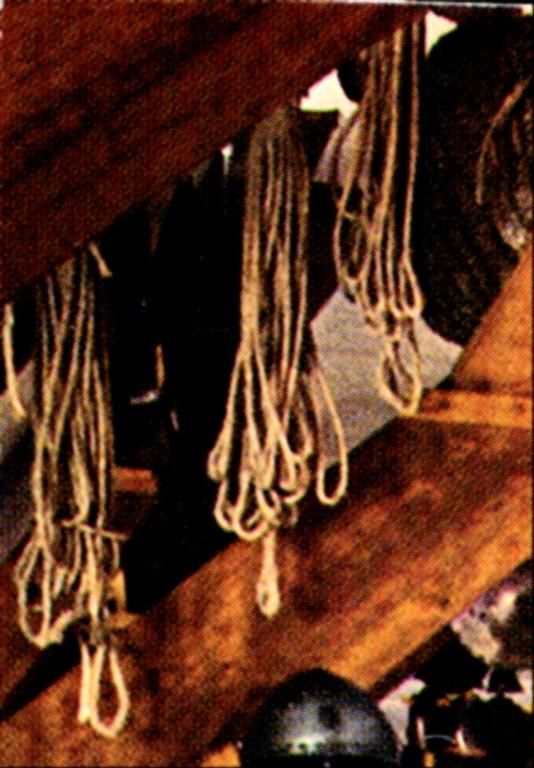

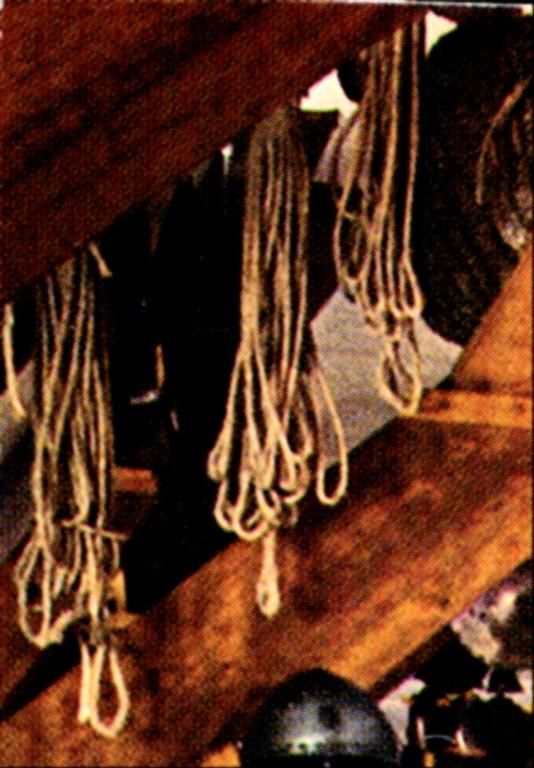

The author was given the chance to closely inspect the bundles preserved at the Fortress Museum (Veste) in Coburg. They measure about 80 cm length in average, each consisting of a great number of loops adding up to a total length of ca. 35-40 m per bundle. Small bundles carried by both musketeers and calivermen only seem to be preserved in the Vienna Arsenal (Heeresgeschichtliches Museum Wien), plus another in the author's collection; they measure approximately two to three meters in length, laid in small loops.

Such small bundles are depicted to be carried by both musketeers and calivermen as 'man's portion' (Mannportion) by Jacob de Gheyn in his famous manual Wapenhandelinghe in 1607.

The author has been assured several times by the leading experts of both museums and international auction houses that, in all probability, he posseses the largest amount of original matchcord in private hands recorded worldwide, including two bundles of ca. 5 m length each, both from the Emden armory, a small Austrian bundle/man's portion of ca. 2,50 m (as mentioned), plus a great number of various lengths from various provenances, and ranging from the 15th/16th to the 17th/18th century, including some considerable lengths of the thickest, rarest and earliest type of matchcord known: from the armory of Schloss Fronsberg, Styria/Austria, sold at auction by Tom Del Mar, London, December 15, 2004.

It is generally assumed that soaked matchcord will consume ca. 60 to 80 cm an hour when smoldering.

The average thickness/diameter of surviving samples of matchcord varies but, consistent both with depictions in period artwork and the Fronsberg samples, seems to have been as thick as ca. 2 cm in earliest times up to the first half of the 16th century, narrowing down to ca. 10-15 mm by the mid-16th century.

It should be noted that in the earliest times of 'matchlock' mechanisms, from ca. 1410 to ca. 1530, matchcord was way too thick to fit the jaws of the rather tiny early matchlock serpentines of the few surviving Late-Gothic and Early-Renaissance arquebuses. Thus it is depicted to be carried glowing by the arquebusier, either held in one hand or wound around the left arm, in pieces of period artwork from ca. 1480 (Diebold Schilling, The Berne Chronicle) to the 1540's (paintings and tapestries of the Battle of Pavia, 1525, and cardboard watercolors of the Tunis Campaign by Charles V and tapestries woven after these cardboards).

In those times, slow match was only used to ignite a small piece of tinder fixed in the jaws of the serpentine of the arquebus: thus, as the aforementioned instances of period artwork clearly depict, and as I have stated various times before, the actual ignition was achieved by glowing tinder and these earliest mechanisms should consequently be called tinderlocks instead of 'matchlocks'.

It is true that tinder stayed in use for both reserve tinder holders on military types of combined wheellock and 'matchlock' mechanisms until at least the early 17th century, and for traditional types of snap tinderlocks for target shooting way up to the mid-18th century. On the whole however, surviving specimens of arquebuses prove that by ca. the mid-16th century, the serpentines - tender and tiny though they still were - could be opened wide enough by turning the wingnuts to receive, and hold, an average thickness of matchcord, which as I have stated had been sufficiently reduced in diameter by that time.

To my knowledge, nobody has cared to do close research in this topic so far.

Matchcord (Luntenstrick), also called slow match or fuse, must have been used for igniting firearms from almost the very beginning. In the earliest two pictorial representations of a gun, the Christ Church and the Holkham manuscripts by Walter de Milemete of 1326/7 (top four attachments) we cannot clearly discern what substance is actually used to ignite the gun; at least in the Christ Church ms it seems to be a somewhat longer and thicker substance much resembling a piece of match clamped in a linstock:

Anyway, matchcord seems to have come into use in the course of the 14th century. For small guns, it is recorded to have been employed until the military end of the matchlock era, which was ca. the 1730's. At that time we find the latest records and drill instructions including service employment of matchlock muskets.

Big pieces, i.e. pieces of artillery/cannon, had of course to be lit by either igniting irons (ca. 14th to 18th c.) or linstocks holding match from the 14th c. until the end of the muzzle-loading era, the mid-19th century.

Slow match basically consisted of three main strands of fibrous hemp including a considerable amount of porous cortex, twisted and soaked in saltpeter/nitrate (Salpeter/Bleizucker). As this chemical solution is volatile it can usuallly no longer be proven in existing pieces of matchcord. However, according to experiments by the author, unsoaked hemp will also smolder constantly to an extent where it can be stopped safely only be either chopping off the glowing end or dipping it into water.

From all we know, matchcord, just like saltpeter (animal urine), was produced by the rural population and purchased by the armories measured by weight. Of course, the dimensions measured up to literally tons. They were handed out to the troops in both larger and smaller bundles.

Surviving large bundles today are extremely few, known only in the armories in both Churburg, Sluderno/South Tyrol, and the Fortress Armory of Coburg/Franconia. A great number of them is known to have been kept in the fortress of Hohenwerfen near Salzburg/Austria but was sold together with the complete contents at auction in New York in 1927.

The author was given the chance to closely inspect the bundles preserved at the Fortress Museum (Veste) in Coburg. They measure about 80 cm length in average, each consisting of a great number of loops adding up to a total length of ca. 35-40 m per bundle. Small bundles carried by both musketeers and calivermen only seem to be preserved in the Vienna Arsenal (Heeresgeschichtliches Museum Wien), plus another in the author's collection; they measure approximately two to three meters in length, laid in small loops.

Such small bundles are depicted to be carried by both musketeers and calivermen as 'man's portion' (Mannportion) by Jacob de Gheyn in his famous manual Wapenhandelinghe in 1607.

The author has been assured several times by the leading experts of both museums and international auction houses that, in all probability, he posseses the largest amount of original matchcord in private hands recorded worldwide, including two bundles of ca. 5 m length each, both from the Emden armory, a small Austrian bundle/man's portion of ca. 2,50 m (as mentioned), plus a great number of various lengths from various provenances, and ranging from the 15th/16th to the 17th/18th century, including some considerable lengths of the thickest, rarest and earliest type of matchcord known: from the armory of Schloss Fronsberg, Styria/Austria, sold at auction by Tom Del Mar, London, December 15, 2004.

It is generally assumed that soaked matchcord will consume ca. 60 to 80 cm an hour when smoldering.

The average thickness/diameter of surviving samples of matchcord varies but, consistent both with depictions in period artwork and the Fronsberg samples, seems to have been as thick as ca. 2 cm in earliest times up to the first half of the 16th century, narrowing down to ca. 10-15 mm by the mid-16th century.

It should be noted that in the earliest times of 'matchlock' mechanisms, from ca. 1410 to ca. 1530, matchcord was way too thick to fit the jaws of the rather tiny early matchlock serpentines of the few surviving Late-Gothic and Early-Renaissance arquebuses. Thus it is depicted to be carried glowing by the arquebusier, either held in one hand or wound around the left arm, in pieces of period artwork from ca. 1480 (Diebold Schilling, The Berne Chronicle) to the 1540's (paintings and tapestries of the Battle of Pavia, 1525, and cardboard watercolors of the Tunis Campaign by Charles V and tapestries woven after these cardboards).

In those times, slow match was only used to ignite a small piece of tinder fixed in the jaws of the serpentine of the arquebus: thus, as the aforementioned instances of period artwork clearly depict, and as I have stated various times before, the actual ignition was achieved by glowing tinder and these earliest mechanisms should consequently be called tinderlocks instead of 'matchlocks'.

It is true that tinder stayed in use for both reserve tinder holders on military types of combined wheellock and 'matchlock' mechanisms until at least the early 17th century, and for traditional types of snap tinderlocks for target shooting way up to the mid-18th century. On the whole however, surviving specimens of arquebuses prove that by ca. the mid-16th century, the serpentines - tender and tiny though they still were - could be opened wide enough by turning the wingnuts to receive, and hold, an average thickness of matchcord, which as I have stated had been sufficiently reduced in diameter by that time.

Canute Rex

40 Cal.

- Joined

- Apr 19, 2012

- Messages

- 397

- Reaction score

- 304

The lead acetate would make the match burn hotter and more slowly. A man named Ulrich Bretscher uses it in his match today: http://www.musketeer.ch/blackpowder/lunte.html

Sidebar - it was also known as "sugar of lead" because of its sweet flavor. It was actually used to sweeten wine.

Sidebar - it was also known as "sugar of lead" because of its sweet flavor. It was actually used to sweeten wine.

RAEDWALD

40 Cal.

Thank you canute and ricky. I will have to add lead acetate making to my skills (yes I am aware of the toxicity).

I am wondering if I should look to making short pieces of hemp matchcord and discard them in a water pot after each discharge. Keeping the continuously lit length in a safe matchcase using it to light a new short piece of match before each shot. In effect as a tinderlock. I have seen period tapestries that clearly show pieces maybe 3 to 5cm long in the serpentines.

Hopefully lead acetate will help to give a brighter coal, with less ash and slower burning.

Might suit a snapping target matchlock where stubbing out the match in the pan from spring pressure wouldn't then matter as it would be discarded anyway?

May you not have matchlock soldiers billeted upon you, so that you can sleep tight.

I am wondering if I should look to making short pieces of hemp matchcord and discard them in a water pot after each discharge. Keeping the continuously lit length in a safe matchcase using it to light a new short piece of match before each shot. In effect as a tinderlock. I have seen period tapestries that clearly show pieces maybe 3 to 5cm long in the serpentines.

Hopefully lead acetate will help to give a brighter coal, with less ash and slower burning.

Might suit a snapping target matchlock where stubbing out the match in the pan from spring pressure wouldn't then matter as it would be discarded anyway?

May you not have matchlock soldiers billeted upon you, so that you can sleep tight.

Canute Rex

40 Cal.

- Joined

- Apr 19, 2012

- Messages

- 397

- Reaction score

- 304

Yulzari,

If you are concerned about safety, you should make a match case and just store the end of the main length of match in it without worrying about short lengths. Look up some pictures of British grenadiers with match cases on their cross belts. You could make something similar if you wanted to keep the match on you.

You could drill holes in the ever useful Altoids tin. I have heard of people simply punching holes in a soft drink can and sticking the match in the top hole.

I do the traditional thing and hold the match between the last two fingers of my left hand. I choreograph my loading movements so the match is never near any powder. Awareness and controlled ritual are better than mechanical safeties, because safeties require awareness anyway.

If you are concerned about safety, you should make a match case and just store the end of the main length of match in it without worrying about short lengths. Look up some pictures of British grenadiers with match cases on their cross belts. You could make something similar if you wanted to keep the match on you.

You could drill holes in the ever useful Altoids tin. I have heard of people simply punching holes in a soft drink can and sticking the match in the top hole.

I do the traditional thing and hold the match between the last two fingers of my left hand. I choreograph my loading movements so the match is never near any powder. Awareness and controlled ritual are better than mechanical safeties, because safeties require awareness anyway.

RAEDWALD

40 Cal.

Canute

I was thinking of a gauze matchcase somewhat like an old miner's lamp.

The short match stub idea came from both seeing the old tapestries and in noting tinderlocks on target matchlocks.

I prefer to go beyond foolproof to soldier proof where I can. A long length of burning double end match cord in one hand whilst loading was a militarily acceptable risk, and the cause of those cool 17th century huge brimmed hats beloved of Civil War musketeers, but I would personally feel more comfortable with all coals being safe while loading and priming. But each to their own.

Drill is a great help and comfort to performance under battle pressure but is no guarantee I have found. In the last year I have twice been interrupted whilst loading my flinter pistol and been left thinking, have I just put in the powder or was it the wadding or either? Also previously that I had put in the ball after being interrupted and then found the charge of powder unused.

As I say, my touchstone is to have systems soldier proof; even Private Towers proof (a certain squaddie of my Company guaranteed to perform any action incorrectly and dangerously.)

I am currently drying some bracket fungus with a view to trying punching out little rods of it to go into a tinderlock serpentine one day.

I was thinking of a gauze matchcase somewhat like an old miner's lamp.

The short match stub idea came from both seeing the old tapestries and in noting tinderlocks on target matchlocks.

I prefer to go beyond foolproof to soldier proof where I can. A long length of burning double end match cord in one hand whilst loading was a militarily acceptable risk, and the cause of those cool 17th century huge brimmed hats beloved of Civil War musketeers, but I would personally feel more comfortable with all coals being safe while loading and priming. But each to their own.

Drill is a great help and comfort to performance under battle pressure but is no guarantee I have found. In the last year I have twice been interrupted whilst loading my flinter pistol and been left thinking, have I just put in the powder or was it the wadding or either? Also previously that I had put in the ball after being interrupted and then found the charge of powder unused.

As I say, my touchstone is to have systems soldier proof; even Private Towers proof (a certain squaddie of my Company guaranteed to perform any action incorrectly and dangerously.)

I am currently drying some bracket fungus with a view to trying punching out little rods of it to go into a tinderlock serpentine one day.

Grizzled Roberts

54 Cal.

- Joined

- Dec 27, 2006

- Messages

- 1,779

- Reaction score

- 12

I once took my big German matchlock on a woodswalk I wrapped the match cord around a tin lantern the lit end went into the tiny opening at the top of the lantern I do not like the idea of the lit match on or near my body while shooting. I had the long gun on one shoulder and the lantern in the other hand. I did not set the woods on fire but I wound up with a few pin sized burn holes in my shirt. Ain't matchlocks fun!

robinghewitt

62 Cal.

- Joined

- Jun 26, 2004

- Messages

- 2,605

- Reaction score

- 22

The lead acetate has a remarkable effect. The hard black "cole" on the end of saltpetre matchcord, which requires knocking off before shooting, becomes a fluffy yellow ash that doesn't get in the way at all.

I have never managed to make a matchcord that will actually light gunpowder :stir: :idunno:

I have never managed to make a matchcord that will actually light gunpowder :stir: :idunno:

Canute Rex

40 Cal.

- Joined

- Apr 19, 2012

- Messages

- 397

- Reaction score

- 304

It's all in the bucking, Squire. My next batch will be double bucked. Get the lignin out and there will be little or no ash to interfere.

The guy who got me into matchlock shooting bucks the living hell out of his own hand braided hemp match and that's it. No saltpeter, no lead acetate, and it develops a big clean cone of red on the end.

The guy who got me into matchlock shooting bucks the living hell out of his own hand braided hemp match and that's it. No saltpeter, no lead acetate, and it develops a big clean cone of red on the end.

I guess you didn't mention the author of the text ... and the images.ricky said:And here is his text on the subject of match cord:

To my knowledge, nobody has cared to do close research in this topic so far. ...

It would be interesting :wink:

JCKelly

45 Cal.

I think the guy who researched all this a decade+ ago was Ultrich Bretscher. His post was about 2007 or so. You can read it now at: http://jaanmarss.planet.ee/juhendid/Tulirelvad/andmebaas/album_tahtlukk/lunte.html

- Joined

- Sep 16, 2019

- Messages

- 217

- Reaction score

- 249

I guess you didn't mention the author of the text ... and the images.

It would be interesting

Some of the text and pictures of armor and match cord may have origins in our beloved Michael Trömner aka "Matchlock" (May he rest in peace). He blogged and published a great number of articles on vikingsword dot com; his authoritative work ought to have been collected and published altogether in book format before his untimely demise.

Rick,

Is that quotation from Michael T? I believe he had the largest supply of original matchcord outside a museum, and indeed more than a great many museums!

Robin,

We can get good hemp here. It's a bit thin but still works well. (below 1/4") I could send you some to play with if you like.

I have used gunpowder, wood ashes, and potash, and they all seem to work.

Richard.

Is that quotation from Michael T? I believe he had the largest supply of original matchcord outside a museum, and indeed more than a great many museums!

Robin,

We can get good hemp here. It's a bit thin but still works well. (below 1/4") I could send you some to play with if you like.

I have used gunpowder, wood ashes, and potash, and they all seem to work.

Richard.

- Joined

- May 24, 2005

- Messages

- 5,522

- Reaction score

- 5,365

Hi Richard

Looks like you found this old Thread. YES !! Michael (Matchlock !) gave me his permission to repost his research for this original Thread. I remember mentioning to him that his research and expertise was too valuable not to let interested shooters become aware. I've always thought one of the best aspects of his personal collection was the wide assortment of original accoutrements. I really miss reading his Threads.

Rick

Looks like you found this old Thread. YES !! Michael (Matchlock !) gave me his permission to repost his research for this original Thread. I remember mentioning to him that his research and expertise was too valuable not to let interested shooters become aware. I've always thought one of the best aspects of his personal collection was the wide assortment of original accoutrements. I really miss reading his Threads.

Rick

Rick,

When Michael wrote a lot of his threads, my old computer couldn't handle all the photos, so when I go back and do a search, I still come up with 'new' info and photos he posted. A bitter-sweet thing really, as there are still so many questions I would have loved to ask him!

Still up to eyeballs in harvest Rick, so not much time here at present...

When Michael wrote a lot of his threads, my old computer couldn't handle all the photos, so when I go back and do a search, I still come up with 'new' info and photos he posted. A bitter-sweet thing really, as there are still so many questions I would have loved to ask him!

Still up to eyeballs in harvest Rick, so not much time here at present...

Similar threads

- Replies

- 13

- Views

- 993

- Replies

- 55

- Views

- 6K