This was written some time back and may be worth a second look. It's long -- sometimes I get carried away.

-----

Shooters here have such wide experiences with cut (sawn) agate that I haven't seen an explanation that satisfies me. I don't like questions that cannot be rationally tested.

So leaving emotion aside, I went back some 25+ years and began looking at experiments that began at the Gunmaking Seminar at Bowling Green KY. I have two possible theories that I want to explore sifting through numbers from those years. The article containing the data is the Journal of Historic Armsmaking Technology, Vol. IV. Jan 1991.

Gary Brumfield was my partner in crime at the beginning. He prodded me into this study. Thanks Gary. The lock that took most of the experimentation was a large Siler with many modifications. (We chose to limit the trials of original locks because of their value.)

The Siler was timed in a variety of ways: multiple flints, bevels, and powders. Buried in this data, may be some answers to our current question.

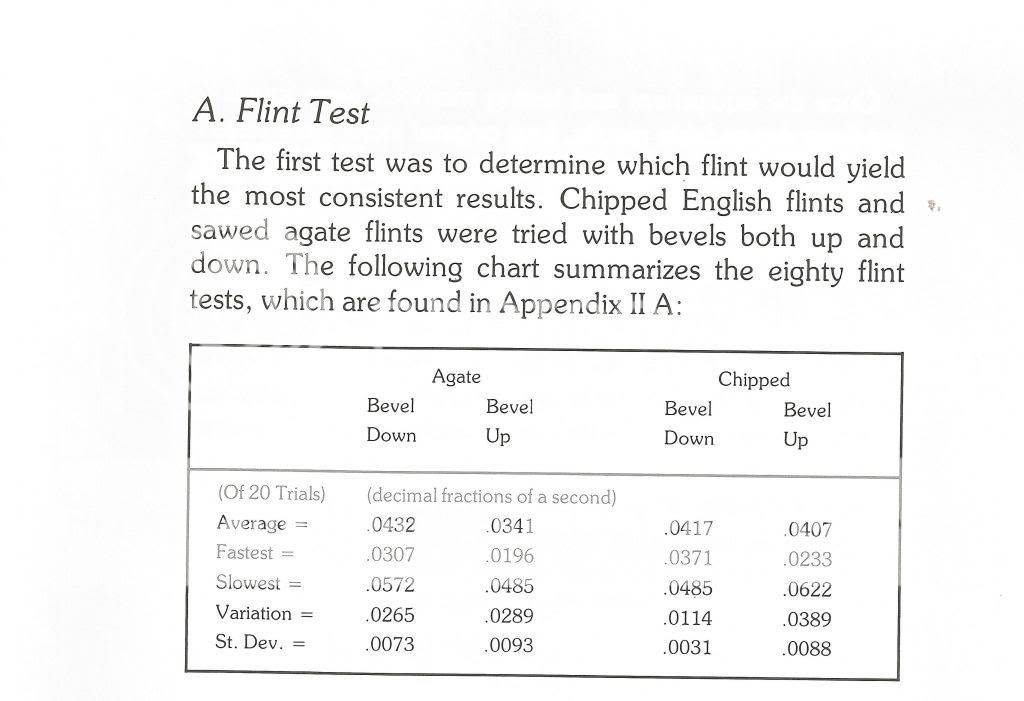

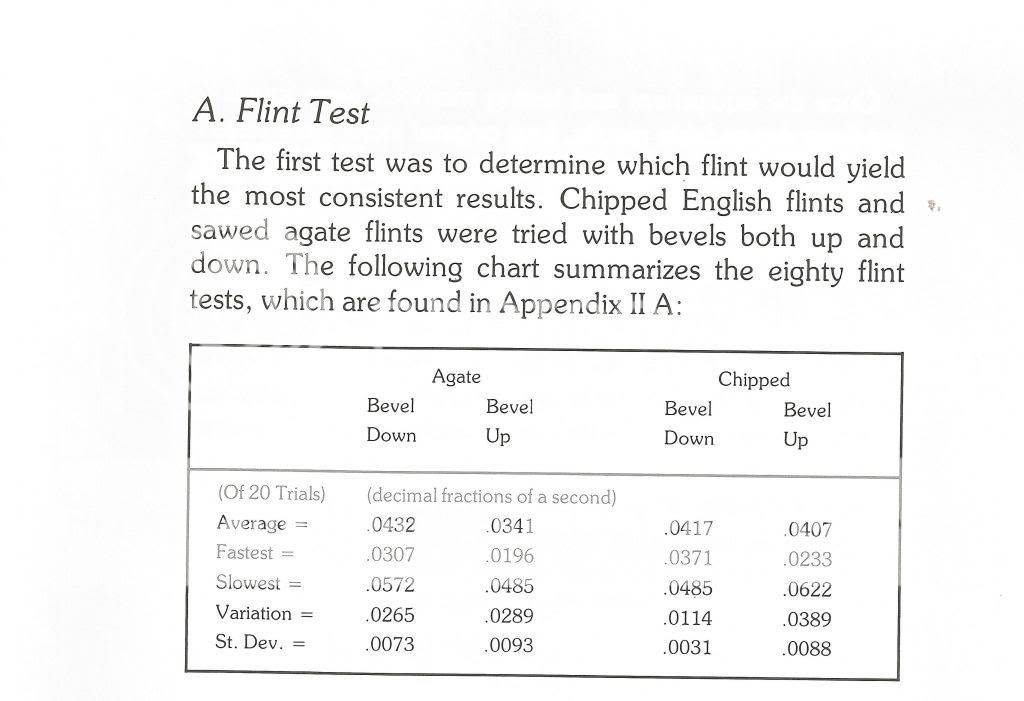

The purpose here is to examine the reasons why sawn agate works for some shooters and does not for others. In looking back at research in the ”˜80s I found a series of trials done with both chipped black English and sawn agate. These opening tests show that this lock performs very well with both types of stones. Below is a brief comment with the flint comparison done in 1987-1988:

First a couple test comments. The lock is a very carefully tuned large Siler. The priming powder is Goex ffffg. Twenty trials were done for each series. Frizzen and flint edges were wiped between trials. Tests were done at room temperatures. Much was done in my school room on weekends.

Notice that the flint averages for bevel up and down are very close. Using chipped flints this lock doesn’t care which way the bevel is used. Bevel up is best when using the agate. Also note that with bevel up the agate was significantly faster than the other three test averages. Notice that the fastest trial was the bevel up agate (.0196 sec). This is so fast that the photo cell many have tripped on the light from sparks alone. For this to happen, spark production must be superb.

The times recorded here are very good. Any lock that approaches .0400 or better is very good. Lots of locks fall between .0400 and .0550. It should be no surprise that after this test, the bevel up agate looks like the way to conduct future tests.

Now, looking at the lack of success that other shooters have with sawn agate, one must ask why. Let’s first rule out sawn “soft stone” sold by some manufacturers. This stone is not in the flint family and isn’t as hard. The ability to sharpen a knife is not a valid test for a stone that sparks well in a flintlock.

I think we should assume that it is not the way the flints are mounted. We’re dealing with experienced shooters. Are we still missing something? The locks are the same brands in many cases. Are there variables we haven’t dealt with? I think there are two.

First are all these sawn agates exactly the same hardness? They are close but not identical. Are all frizzens exactly the same hardness? Are they all heat treated in the same batch by the same operator? No, they may be close, but not the same.

Dealing with the stones, flint, agate, chert, etc are part of a mineral group (complex silicates) that are number 7 on Mohs hardness scale. The scale is a 1 to 10 scale with talc at number 1 and diamond at 10. Steel is often thought of at 5.5. In a theoretical world all steel is 5.5 and all flint and agate is exactly 7. But, in the real world these numbers vary. All frizzens are NOT 5.5, and flint and agate are NOT 7.

I would guess that a mismatch of frizzen and stone could cause some of these problems. I have no way to measure the precise hardness of flint and agate, nor the exact hardness of frizzens. Maybe the Rockwell number system can help with frizzens, but I know of no way to get a finer number for the stones.

I guess I’m back where I started. My gut says the answer lies with the relative hardness of the frizzen and the stone. Swapping frizzens might be interesting. Perhaps a frizzen swap might make an agate-loving lock into an agate-hating lock. Regardless of which is the problem, shooters will continue to do as they have been doing. They will find the stone type that works and install it to best advantage. They will avoid the soft stone regardless if it is chipped or sawn.

Final thoughts: In geology class we used the stainless steel watch back to judge hardness in the field. If a stone won’t easily scratch your watch back, it won’t spark reliably in your lock. Don’t assume that any sawn stone is agate. Most likely it is soft sharpening stone. The sawn product from Germany is agate and performed well in my tests. The bevel up agate test was one of the fastest Silers I’ve timed.

I didn’t mean this to be this long. One idea led to another. I did decide to upload the JHAT article if the NMLRA will give permission.

Regards,

Pletch