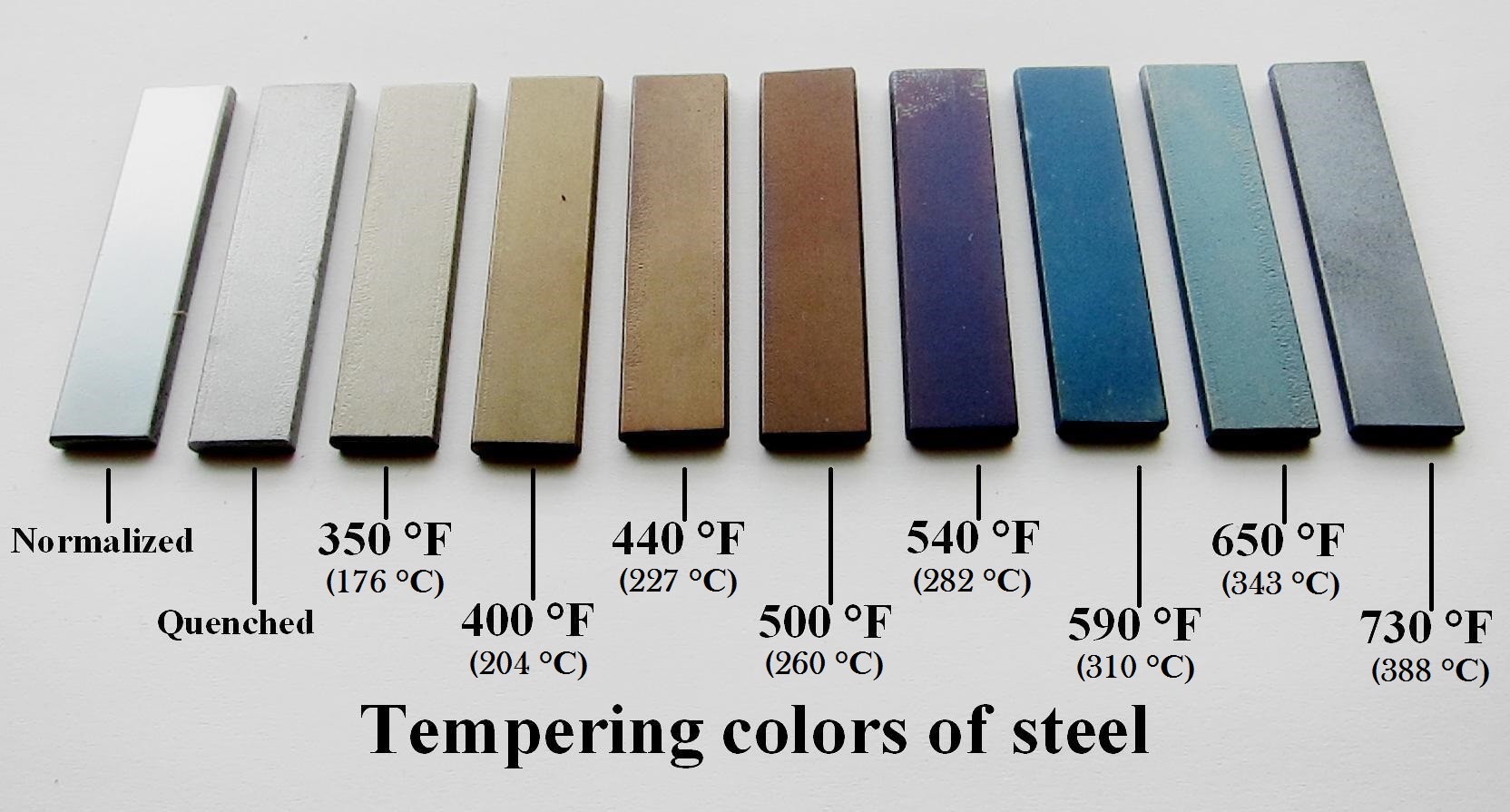

The colors I've seen at around the 590°F temperature is a brilliant, vivid blue. Almost, in my opinion, to bright for a barrel finish although you might like it.

I often use heat bluing for the screw heads on the guns I've built and like the color that is between the purple 540° and the bright blue around 590°.

Around 560° - 570° a very dark, rich blue color emerges.

I have had problems trying to heat blue very large things like gun barrels with a propane torch. It is all too easy to slightly overheat an area with a torch and end up with a mottled assortment of dark and light areas. Even if you heat the barrel very slowly, creeping up on the color you want, it's hard to stop the color change at exactly the same blue color.

The factories that use heat bluing on their guns do it in furnaces with every exact heat control systems on them.

Anyone interested in using heat bluing should try it on a button head screw. Make sure the surface is lightly sanded and totally oil free. Then, working under a bright light, very slowly heat the metal while you hold the screw with a set of locking pliers. Watch the surface constantly and carefully as it changes color.

The instant it changes to the color you want, quench the metal in a light oil.

If you don't like the color, sand it off and try again.