- Joined

- Feb 18, 2019

- Messages

- 102

- Reaction score

- 212

I saw a percussion rifle this weekend that looked to be mid to late 19th century. The barrel was stamped CAST STEEL PITTSBURG. Does anyone know anything about cast steel barrels?

Good and accurate report on the subject. The Besseymer "SP" process of cast steel production of English origin I believe was the real game changer in quality carbon steel and I think it was Sheffield of England that first offered quality cast steel barrels. Later Remington offered them as well and the top barrel makers in this country used them in their match barrel making.Cast steel became available with the introduction of steel production by the crucible method. Previously, it was not possible to control the amount of carbon in iron made by casting or in wrought iron made from a 'bloom' of iron ore. Steel was formerly made in small batches by case hardening of wrought iron or by the 'blister' method. When crucible steel was introduced, it became possible to produce larger items from steel, per-se. The crucible was poured to become a casting which could then be forged into various shapes, including bars suitable for barrel making, thus eliminating the need to weld-up the barrel blank from separate bars or scelps of wrought iron, though the bar had to be drilled through to establish the original bore. The homogenous structure of the cast steel was superior to welded wrought iron, and gave a potentially stronger and safer finished barrel. The cast steel used in barrel making was a mild steel, and did not need further heattreatment for use in black powder arms, but could also be case hardened for wear-resistance in lock parts, etc. Cast steel (or carbon steels as a class) are said to be less rust-resistant than wrought iron, but that need not be a concern with proper care and cleaning.

mhb - MIke

Cast steel became available with the introduction of steel production by the crucible method. Previously, it was not possible to control the amount of carbon in iron made by casting or in wrought iron made from a 'bloom' of iron ore. Steel was formerly made in small batches by case hardening of wrought iron or by the 'blister' method. When crucible steel was introduced, it became possible to produce larger items from steel, per-se. The crucible was poured to become a casting which could then be forged into various shapes, including bars suitable for barrel making, thus eliminating the need to weld-up the barrel blank from separate bars or scelps of wrought iron, though the bar had to be drilled through to establish the original bore. The homogenous structure of the cast steel was superior to welded wrought iron, and gave a potentially stronger and safer finished barrel. The cast steel used in barrel making was a mild steel, and did not need further heattreatment for use in black powder arms, but could also be case hardened for wear-resistance in lock parts, etc. Cast steel (or carbon steels as a class) are said to be less rust-resistant than wrought iron, but that need not be a concern with proper care and cleaning.

mhb - MIke

I bought this rifle from the widow of a club member. It was the very last rifle sold by Jackson Arms in Dallas, Tx when Elsie Jackson closed the business in 1993. It is in really good shape. I feel that it was made to shoot a Pickett bullet. The barrel is 36” x 1”, 36 caliber. The maker Daniel J. McDonald is listed in American Gunsmiths as having died in 1864.

plmeek:Mike, I agree with much of what you say about "cast steel", especially the interchangeability of the terms "crucible" or "cast" steel. The use of the term "cast steel" in the first half of the 19th century reflected the manner in which it was made. The term had nothing to do with "casting" steel in molds.

A Short History of Steel

I do beg to differ with the statement I highlighted in bold above. Deep hole drilling, aka gun barrel drilling, did not become a common practice in gun making until the last quarter of the 19th century. It appears to have originated in Europe, likely Germany.

History of Gundrilling

The US armories--Harper's Ferry and Springfield--were likely the first in North America to experiment with gun barrel drilling, post Civil War.

Muzzleloader barrels marked "cast steel" would have still been forge welded from skelps around a mandrel to establish the bore of the barrel. Then the bore would have been reamed out on a boring table and finally rifled on a rifling table.

There was a lot more technology the was yet to be developed to make gun barrel drilling practical.

This thread on another forum shows typical metal drill bits used in gun making in the 18th and early 19th century.

18th and early 19th century metal drill bits

As the intro in the above linked thread says, "Twist drill were not used prior 1860." The biggest challenge in deep hole drilling was keeping the hole straight. Other challenges included removing the cuttings from a deep hole and keeping the drill bit cool.

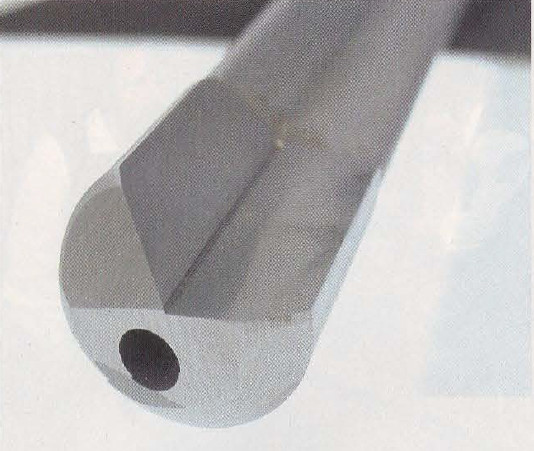

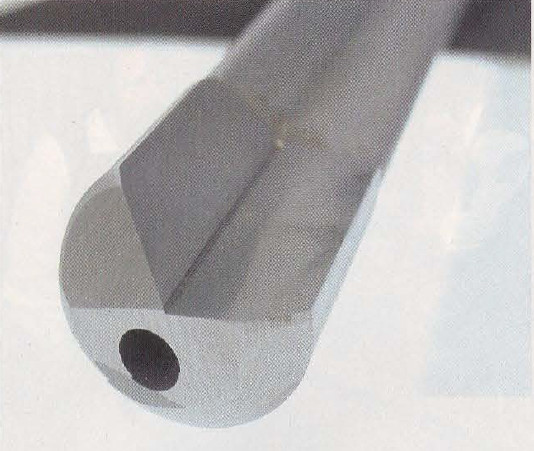

These challenges were finally overcome with the development of a drill bit that resembled the one shown below.

A single cutting edge and a long bearing surface helped to keep the hole straight. A hollow tube connected to the bit with a hole near the tip allowed cutting fluid to be pumped to the drill face to cool the bit, lubricate, and flush cuttings up and out of the hole. The relieved quarter section of the drill bit provided a place for the cuttings to go and be pumped out with the cutting fluid.

Trial and error showed that rotating the barrel stock while holding the drill bit stationary resulted and a straighter and more uniform hole.

Enter your email address to join: