A few folks appear to be citing information from memory and inadvertently misrepresenting the facts.

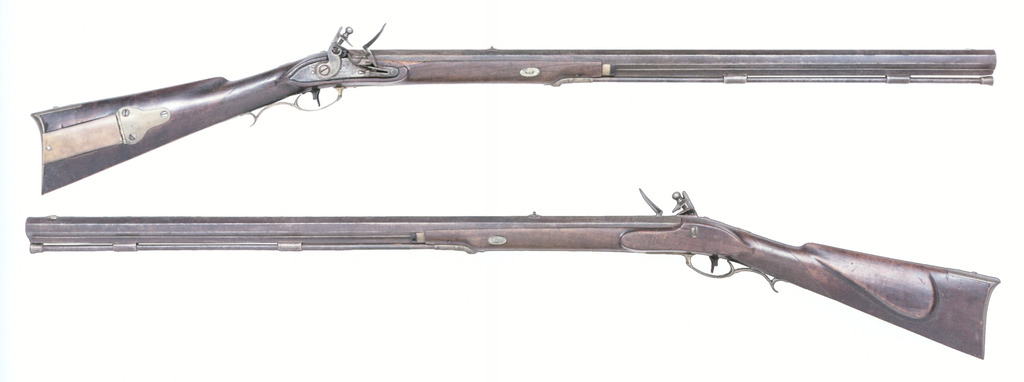

There have been no half stock or full stock flintlock rifles (in any caliber) Hawken stamped rifles located. There are a couple of Hawken stamped rifles that have a percussion lock that may be a converted flint lock, but the barrel appears to have always been percussion. None of the orders from the fur trade era have specified a flint lock Hawken, always percussion...The book, "The Hawken Rifle: Its Place in History" by Charles Hanson goes into far more detail than we would want to go into on the forum.

"There have been no half stock or full stock flintlock rifles (in any caliber) Hawken stamped rifles located." This statement requires a lot of qualification. I believe I know what

Grenadier1758 is saying, but it would help if he was a little more explicit for people who are less familiar with the Hawken brothers and their rifles. There are Hawken marked rifles that are or were originally flintlocks. Some of them just weren't made in St. Louis. This one is marked "S Hawken" in script and was likely made in Hagerstown, MD or Xenia, OH.

There is also a "C & J Hawken" marked rifle that was flintlock, now converted to percussion. Both of these rifles are now in the James Gordon collection.

"There are a couple of Hawken stamped rifles that have a percussion lock that may be a converted flint lock, but the barrel appears to have always been percussion." This statement is not supported by published information.

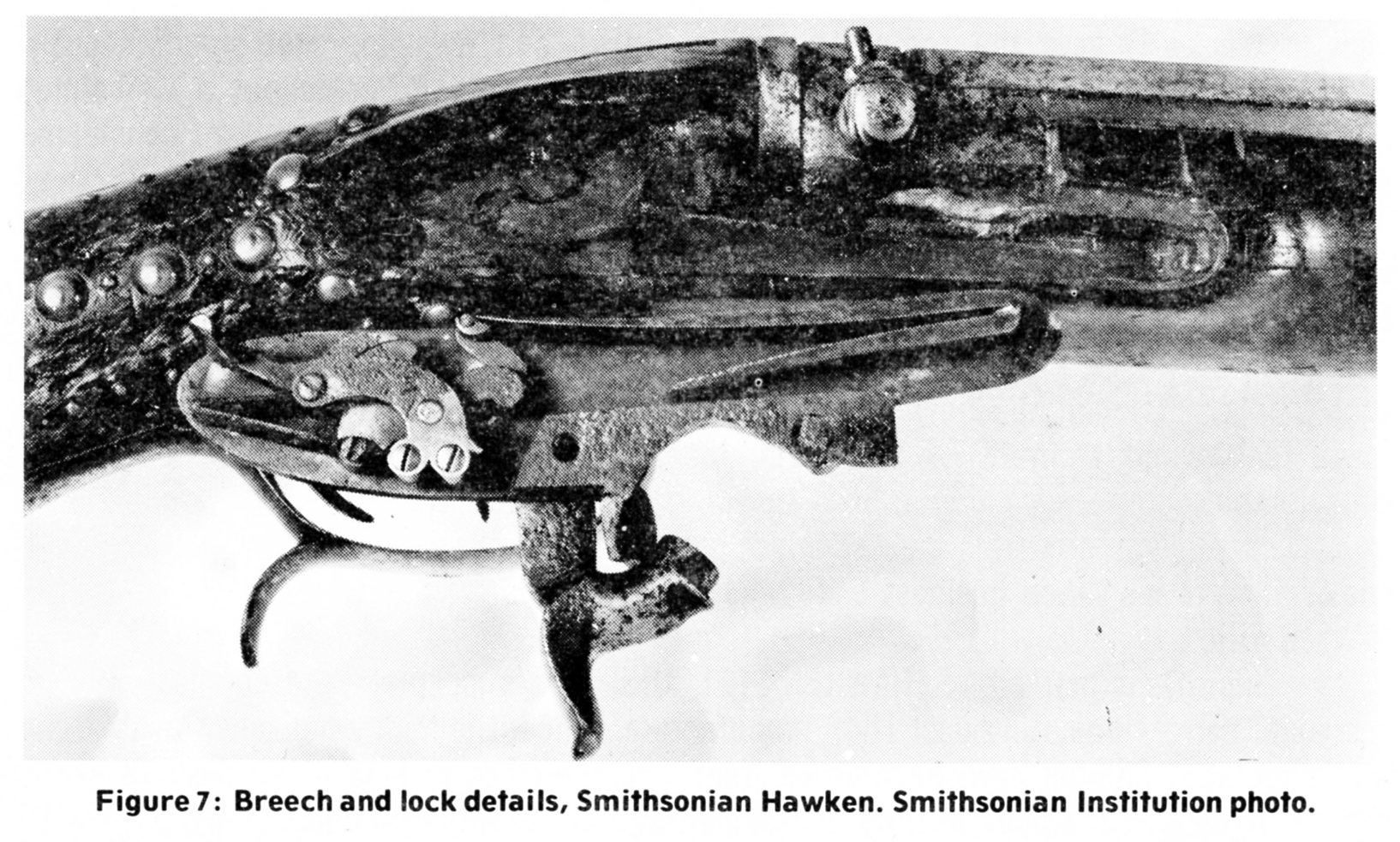

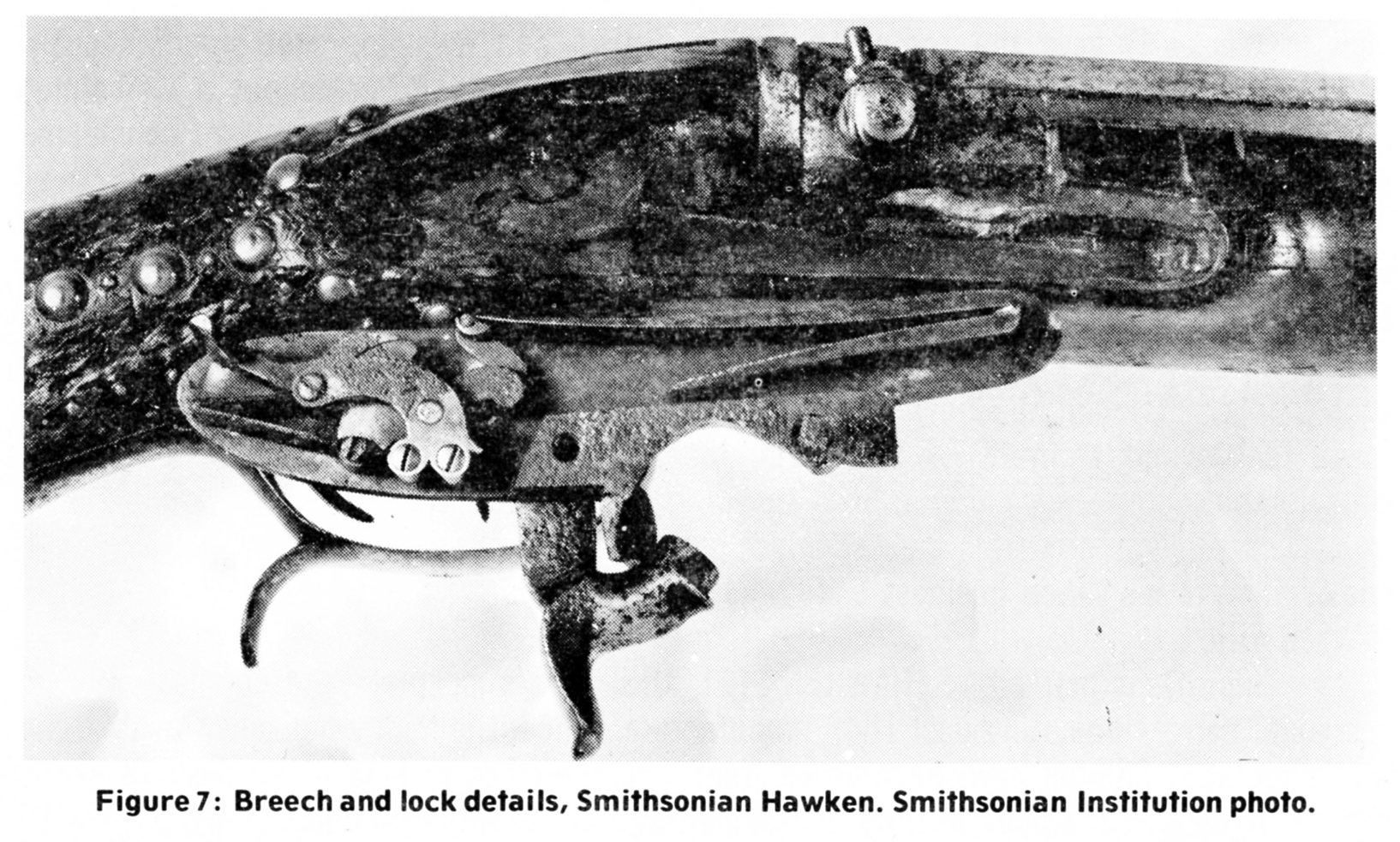

The Museum of the Fur Trade Quarterly - Winter 1977 published an article by John T Powell on the Kennett Hawken Rifle and the Smithsonian Hawken Rifle. The author requested that the Smithsonian examine the S. Hawken in their collection and answer a number of questions about it. Powell wrote, "After careful examination personally and with additional consultation from without the Institution, Mr. Goins [of the Smithsonian Institution] advised that the rifle was now percussion but had definitely been a flintlock in its original form." Mr. Powell also writes, "This lock was not engraved; does not appear to have been a commercial product, and has every appearance of being fabricated in the same shop as the Kennet Hawken [likely the Hawken shop]."

This is not the best quality photo, but I see nothing in it to suggest that "the barrel appears to have always been percussion". In fact, I don't know how one would tell from the barrel alone that it had always been percussion. There are often signs that a rifle had been flint, then converted to percussion, and later re-converted back to flint. The fulminate from the percussion caps often corrodes the barrel around and forward of the nipple. It can also affect the wood of the stock.

On another forum, a person relayed second-hand information that the stock did not show any evidence of having a cut out for a cock on the lock panel. The Smithsonian Hawken was made in the 1850s. At the end of the flintlock period, one of the last flint lock styles developed did not have the cock stopping on the top of the lock bolster. These locks had double throated cocks that were designed for the cock to stop on the rear fence. There was no need for a cut out on the lock panel. The Hawken shop could have copied one of these very late flintlocks for the Smithsonian Hawken.

Another published report on the Smithsonian Hawken was presented in the December 1977 issue of

Buckskin Report. In it John Baird wrote a letter to Col. Vaughn Goodwin, who was active in the NMLRA and contributor to

Muzzle Blasts, asking Goodwin's opinion on several points concerning the Smithsonian Hawken. Baird was setting Goodwin up because Baird already knew the answers and was hoping Goodwin would take the bait and make a fool of himself concerning the question about whether the Smithsonian Hawken had originally been flint or not.

This is Goodwin's response to Baird.

Baird then proceeded to show a number of close-up pictures of the Smithsonian Hawken refuting all of Goodwin's points. In fact, the reader is left with the impression that Goodwin had never inspected the Smithsonian Hawken, at least not as closely as he claimed. The whole report covered six pages in the magazine. This is the last page where Baird sums of the analysis and expresses his opinion that the rifle was originally a flintlock.

"None of the orders from the fur trade era have specified a flint lock Hawken, always percussion." This statement is only half true. It should say that none of the orders from the fur trade era mentioned whether the Hawken rifles were flint or percussion. Hanson only found a couple of orders that distinguished between full stock and half stock and none that distinguished between flint and percussion. There is an invoice for the 1836 rendezvous that listed "10 boxes" of percussion caps. A box likely contained 1,000 caps. The invoices also lists 12 Hawken rifles, but does not specify if they are flint or percussion.

There is also a surviving letter, dated January 2, 1829, by Kenneth McKenzie requesting Pierre Chouteau, Jr. to “Please add to the spring order two Rifles similar in all respect to the one made by Hawkins for Provost.” McKenzie saw Etienne Provost with his Hawken rifle in 1828 at either Fort Union or Fort Tecumseh or both. Provost likely bought his Hawken rifle in 1827 for he spent the last half of that year in St. Louis before going up river and on to the mountains in early 1828.

Considering the dates, Etienne Provost's Hawken would have certainly been a flintlock.

When studying the plains rifle you should also look at Henry Leman rifles, his company made more rifles on Friday than the Hawken boys did in all their career.

His design went from trade guns, to fowlers, to long guns, to plains rifles. He produced rifles from the early 1800's up until his death in 1885.

The Leman company produced flintlock rifles into the 1900's

At one time Leman had almost 400 people working for him...

Fred

Ignoring the obvious hyperbole in the statement about "his company made more rifles on Friday", there are other lapses of memory.

Henry Leman started his business in 1834. Charles Hanson, Jr. in a paper presented at the

American Society of Arms Collectors and published in their bulletin as well as published

The Museum of the Fur Trade Quarterly - Winter 1984, states that Leman produced 250 rifles in his first year and had an early order from a St. Louis merchant for 50 rifles to be used in the Indian trade. Leman received a contract from the government's Bureau of Indian Affairs for 500 rifles in 1837. In 1842, he started supplying the BIA with NW trade guns, but made no more rifles for the government. He also never had any business with the American Fur Company. He sold the bulk of his rifles directly to merchants scattered around the country. Leman rifles didn't make it west until late in the mountain man period and in numbers not that much greater than the Hawken brothers. His production increased with those government contracts, and he became the largest supplier of trade guns and rifles in the 1850s through the 1870s.

The 1850 census reported that Leman had 34 employees with an annual production of 5,000 gun barrels and 2,500 complete guns. By the 1860 census, he had almost doubled those numbers with 62 workers and 5,000 guns. There's no indication that he "had almost 400 people working for him."

Henry Leman died in 1887, and his factory, which had declining business for the past decade, shut down with his death. It did not operate into the 1900s. That was the Tryon's.