I've had good luck with this type of patience when removing difficult, stubborn, and stuck screws. I found on my Pedersoli 1766 Charleville, the Jim Chambers combo tool is a perfect fit for the slots on the tumbler/cock (hammer) screw, and the lock screws. It is hardened too. If I had any of these screws to remove on an original musket and they were seized, rusted badly, I would do what Gus has suggested. If you have access to a drill press, I would probably modify the combo-tool so I could use it in the drill press chuck (this is an old gunsmith trick been used probably ever since drill presses been around). By doing that I would ensure the tool couldn't so easily slip and twist UP and out of the slot. I will post some pictures below of the tool I speak of. You can see it has a square area in the center of the blade where the extension screws on. You can do this with modified screwdrivers as well.

View attachment 10054View attachment 10055 View attachment 10056

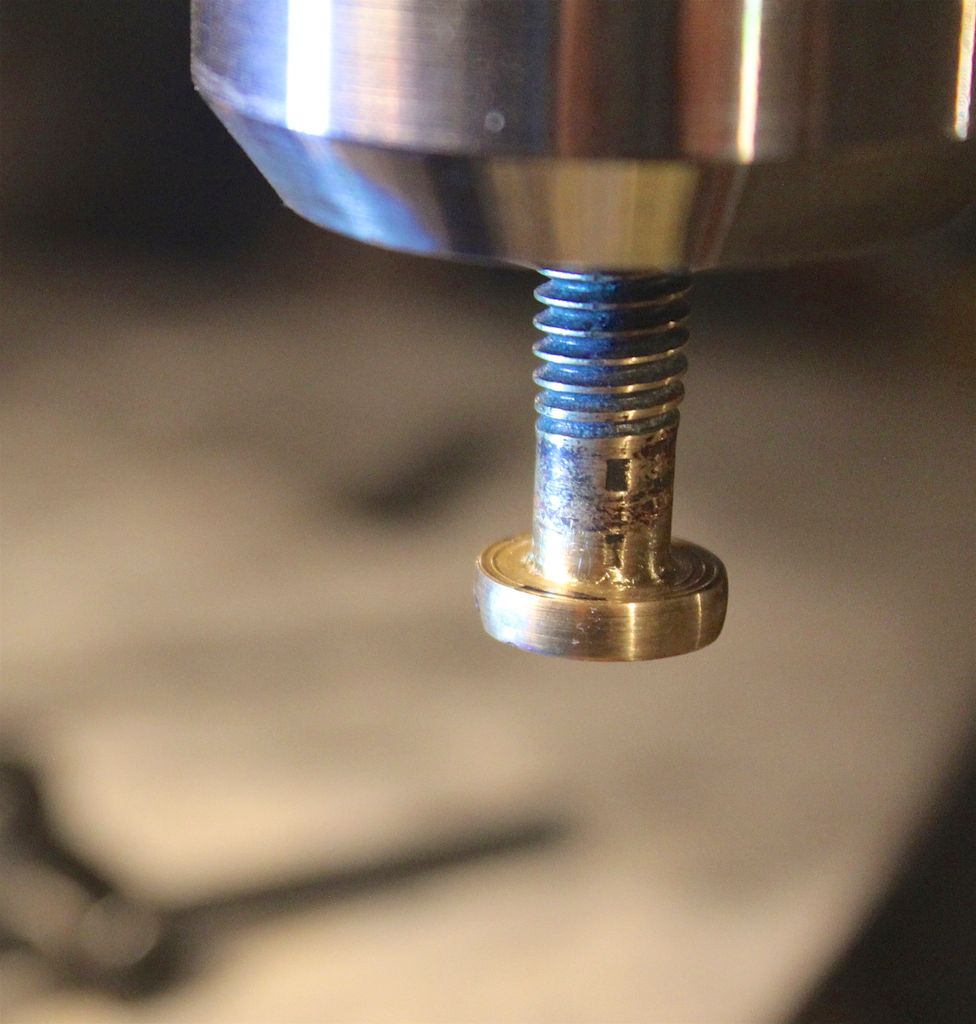

Below is mine with adapters for use on the Charleville. I would probably have to grind or file the hammer at the head so it is the same diameter os the round boss just above the square piece, but maybe not. I'd put hte chuck jaws on the top of the square piece. By putting slight pressure on the tool with the drill quill, and locking it in place, you can then use a wrench on the square part to turn the screw. On my tool, I might have to true up the screwdriver flat so it is perpendicular to the hammer head part, mine appears to be at a slight angle. In any event this is some food for thought. This tool seems like it was almost made for this kind of work. If you look closely at the picture you can see the thin slot marks from my drill press chuck on the brass adapter extension. I've used it to polish screws heads, and in my cordless DeWalt hand drill to polish the bore with a extra long bore mop made for that chore. Not a mirror polish.

View attachment 10057 View attachment 10058 View attachment 10059

I don't know how wide the slots on original muskets were. You can get some idea of the size of mine on the David Pedersoli reproduction. This lock was disassembled and tuned by me, so all screws have seen a screwdriver, some more than once.

View attachment 10061

View attachment 10063

Good luck with the project. Dave Person probably has a whole bag of tricks of this sort to remove seized screws. He restores badly, and I mean BADLY abused, reenactor's muskets, especially Brown Bess's that have never had the action or barrel removed! He has in depth tutorials posted on the forum. Amazing stuff. He's taken muskets that were what I would have thought a total loss, buggered up, banged up, corroded and abused, and restored them to HC works of art! His encouragement and help on my lock tune were invaluable. Let us know how things progress with the seized actions on those old muskets please.

George