user 56333

40 Cal

- Joined

- Dec 30, 2022

- Messages

- 156

- Reaction score

- 122

I apologize for harping on about the First Opium War here, but I admit it's one of the few historical cases of matchlocks vs. flintlocks that I actually know about.

I was having a look through "Narrative of the Voyages and Services of the Nemesis from 1840 to 1843" (which is a great firsthand account written by a Brit who was there) and found a few interesting quotes in relation to the Chinese use of matchlocks, which may provide a contrast to what folks here know about how the Brits handled flintlocks and caplocks during this period.

Here's a quote which describes the accidents I referred to earlier around the manner in which the Chinese carried their powder:

"[matchlocks are] by no means so much in favour with the Chinese; this is occasioned principally by the danger arising from the use of the powder, in the careless way in which they carry it. They have a pouch in front, fastened round the body, and the powder is contained loose in a certain number of little tubes inside the pouch, not rolled up like our cartridges.

Of course, every soldier has to carry a match or port-fire to ignite the powder in the matchlock when loaded. Hence, when a poor fellow is wounded and falls, the powder, which is very apt to run out of his pouch over his clothes, is very likely to be ignited by his own match, and in this way he may either be blown up at once, or else his clothes may be ignited; indeed, it is not impossible that the match itself may be sufficient to produce this effect. At Chuenpee, many bodies were found after the action not only scorched, but completely burnt, evidently from the ignition of the powder."

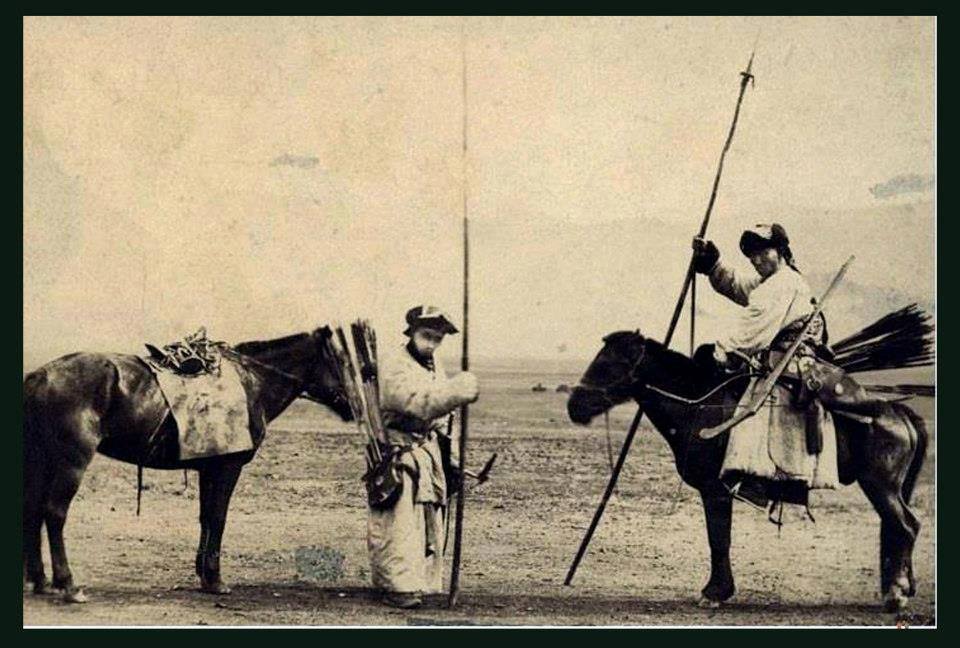

And here's a quote from an engagement in which British troops were trying to dislodge "Tartars" (soldiers from northern China, possibly Manchus or Mongols) from a building, which indicates the potential hazards of leaving a matchlock and lit match unattended:

"It was next proposed to set the place on fire, for on one side the upper part of the building appeared to be built of wood [...] The fragments of the wood-work, which had tumbled down, were now collected into a heap by the sappers, and set on fire, which soon communicated to the rest of the building. Gradually, as it spread, the matchlocks of the Tartars (probably of the fallen) were heard to go off, and loud cries were uttered. The rest of the defenders must evidently surrender; and, on entering the doorway, the poor fellows could now be seen stripping off their clothes to avoid the flames, and running about in despair from one side to the other."

One thing I've noticed is, when the author of this book describes specific incidents of British soldiers being wounded by Chinese matchlock fire, it seems they were often hit low. For instance, he mentions an example of a soldier from the Royal Irish Regiment being hit in knee, and another of an officer from the 55th Regiment of Foot being wounded (ironically) in the foot. Of course, a more thorough examination of battle wounds from this conflict would be needed to determine whether there was any consistency to this, but it does make me wonder if perhaps the matchlock muskets used by the Chinese had a tendency to shoot low for some reason?

I'm unsure if there was any particular pattern to how the British flintlock and caplock guns in service during this era (late 1830s / early 1840s) tended to hit their target, but if anyone here knows, it'd be interesting for comparison's sake.

I was having a look through "Narrative of the Voyages and Services of the Nemesis from 1840 to 1843" (which is a great firsthand account written by a Brit who was there) and found a few interesting quotes in relation to the Chinese use of matchlocks, which may provide a contrast to what folks here know about how the Brits handled flintlocks and caplocks during this period.

Here's a quote which describes the accidents I referred to earlier around the manner in which the Chinese carried their powder:

"[matchlocks are] by no means so much in favour with the Chinese; this is occasioned principally by the danger arising from the use of the powder, in the careless way in which they carry it. They have a pouch in front, fastened round the body, and the powder is contained loose in a certain number of little tubes inside the pouch, not rolled up like our cartridges.

Of course, every soldier has to carry a match or port-fire to ignite the powder in the matchlock when loaded. Hence, when a poor fellow is wounded and falls, the powder, which is very apt to run out of his pouch over his clothes, is very likely to be ignited by his own match, and in this way he may either be blown up at once, or else his clothes may be ignited; indeed, it is not impossible that the match itself may be sufficient to produce this effect. At Chuenpee, many bodies were found after the action not only scorched, but completely burnt, evidently from the ignition of the powder."

And here's a quote from an engagement in which British troops were trying to dislodge "Tartars" (soldiers from northern China, possibly Manchus or Mongols) from a building, which indicates the potential hazards of leaving a matchlock and lit match unattended:

"It was next proposed to set the place on fire, for on one side the upper part of the building appeared to be built of wood [...] The fragments of the wood-work, which had tumbled down, were now collected into a heap by the sappers, and set on fire, which soon communicated to the rest of the building. Gradually, as it spread, the matchlocks of the Tartars (probably of the fallen) were heard to go off, and loud cries were uttered. The rest of the defenders must evidently surrender; and, on entering the doorway, the poor fellows could now be seen stripping off their clothes to avoid the flames, and running about in despair from one side to the other."

One thing I've noticed is, when the author of this book describes specific incidents of British soldiers being wounded by Chinese matchlock fire, it seems they were often hit low. For instance, he mentions an example of a soldier from the Royal Irish Regiment being hit in knee, and another of an officer from the 55th Regiment of Foot being wounded (ironically) in the foot. Of course, a more thorough examination of battle wounds from this conflict would be needed to determine whether there was any consistency to this, but it does make me wonder if perhaps the matchlock muskets used by the Chinese had a tendency to shoot low for some reason?

I'm unsure if there was any particular pattern to how the British flintlock and caplock guns in service during this era (late 1830s / early 1840s) tended to hit their target, but if anyone here knows, it'd be interesting for comparison's sake.

Last edited: