Charles, I fear your original question about rifles got lost in all of this, so here are a few generalities that might help you with your selection. Hopefully Mike Brooks or one of the other superb builders we have on here will step forward with any corrections to these:

Ӣ Early Longrifles (pre-Rev War) were typically wide at the butt, up to as much as 2" wide with little curve to the butt-plate. They usually were 50 cal. or larger though specific caliber was inconsistent because hammer welding rifle barrels did not produce truly consistent rifled bore sizes. Thus, each rifle came with a mold to cast the ball for that barrel.

These were smaller calibers than the German Jaeger rifles which virtually all the early gunsmiths had experience making in Germany that were typically .62 caliber in size. During the war the butt-pieces became a little narrower. After the war they became narrower yet and the crescent style of butt-piece became prominent as it moved into the Golden-Age rifles (1790-1830 or so).

Ӣ After the war the caliber of longrifle dropped with lots of .45 and .40 caliber rifles made. During the war a .40 caliber rifle would be very unusual.

Ӣ Early rifles usually had some carving of some sort on them. At least incise carving, though relief carving in the Rococo style was common. During the war, most surviving example have relief carving. About the only ornamentation on them would be a hunting star on the cheekpiece and perhaps a medalion as a thumbpiece on top of the stock behind the tang. Highly ornamented rifles with brass ornamentation around the wrist and along the forend did not show up as normal until the golden age after war, when the demand for rifles plummeted (no more war) and gunsmiths had to do something special to make their pieces stand out and sell.

Ӣ Early longrifles either had no patchbox or had a sliding wooden patchbox prior to the war. Simple brass patch boxes came out right before the start of the war and progressively became more ornamental. Sliding wooden patchboxes were still common in the early war. "Daisy" pattern patchboxes were seen during the war, but "pierced" patchboxes didn't appear until after the war. Pierced patchboxes are those that have wood showing through the brass patchboxes as part of an ornamental pattern instead of the patchbox being solid brass in whatever shape was used.

Ӣ The wrist of the longrifle was always significantly wider than it was tall to make sure there was plenty of strength in the wrist to withstand the heavy loads needed for 50 to 62 caliber round balls. Wrists thinned out some after the war as caliber size went down and powder charges reduced accordingly. However, they never became narrow and tall as you often find now in production rifles.

Ӣ All of the original longrifles I've seen had very slender forends. The front stock was not very deep. That is perhaps a fine point, but most of the production longrifles have very thick fore-ends and you could easily take half the wood off the forend to get them closer to what they should be.

”¢ Rifle barrels varied in length with Haynes Lancaster rifles being short at 38" while more of them were 42 to 44½" in length. So plenty of room to play with there. Capt. John Warner of the Green Mountain Rangers had an exceptionally long rifle at 7-ft. in length. He used it at the Battle of Bennington. That was an unusual rifle. So basically any barrel from 38" to 44½" in length would definitely fall into the Rev War period.

Ӣ All barrels until the 1820's were hammer forge-welded and were swamped barrels. Straight and tapered barrels didn't appear until automatic machinery began making barrels (I believe that was the 1820's...not sure). A swamped barrel is night and day easier to mount, sight, hold on target, and just all around handle than a straight or tapered octagon barrel. I have both and there is absolutely no comparison in my opinion. Nonetheless, no one will give you pause if you don't have a swamped barrel. They are typically an extra $100 to $150 over the standard barrels and worth every penny of it.

Ӣ Barrels at the time were either finished "in the white", or were charcoal blued, which was a high-heat blued finish. The natural "in the white" barrels developed a natural patina with use, but are nowhere near being a "browned" barrel. Browning barrels didn't become popular until after the war. A blued barrel, bright barrel, or natural patina barrel would be typical but again, no one is going to give you grief if yours is browned.

Ӣ Early locks were either German or British as the colonists were prohibited from manufacturing locks. That doesn't mean we didn't do make them, but we tried not to get caught doing so. British locks came in by the barrel-full and were commonly and widely used prior to the war. If Mike Brooks pipes in, he can give you a lot more info about locks used from 1775-1783.

Ӣ Triggers can be either single trigger or double trigger (set trigger) designs as both were used during the war.

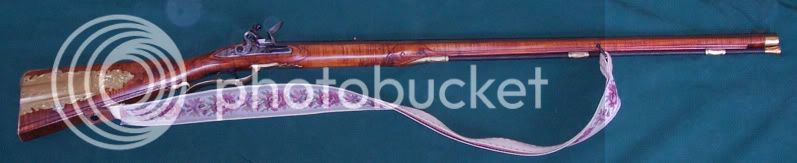

So there's some general guidelines to help you out. The rifle I use is an early Lancaster made by "tg" from here on the forum. With its Queen Anne lock (originally made from about 1720-1760) would be considered an early longrifle, pre-war. By the way, did I tell you what a beautiful job he did on it? I use it mostly for Rev War Reenactments, but hunt with it too. It draws admiring comments at almost every event I attend.

Anyway, hope this helps.

Twisted_1in66 :thumbsup:

Ӣ Early Longrifles (pre-Rev War) were typically wide at the butt, up to as much as 2" wide with little curve to the butt-plate. They usually were 50 cal. or larger though specific caliber was inconsistent because hammer welding rifle barrels did not produce truly consistent rifled bore sizes. Thus, each rifle came with a mold to cast the ball for that barrel.

These were smaller calibers than the German Jaeger rifles which virtually all the early gunsmiths had experience making in Germany that were typically .62 caliber in size. During the war the butt-pieces became a little narrower. After the war they became narrower yet and the crescent style of butt-piece became prominent as it moved into the Golden-Age rifles (1790-1830 or so).

Ӣ After the war the caliber of longrifle dropped with lots of .45 and .40 caliber rifles made. During the war a .40 caliber rifle would be very unusual.

Ӣ Early rifles usually had some carving of some sort on them. At least incise carving, though relief carving in the Rococo style was common. During the war, most surviving example have relief carving. About the only ornamentation on them would be a hunting star on the cheekpiece and perhaps a medalion as a thumbpiece on top of the stock behind the tang. Highly ornamented rifles with brass ornamentation around the wrist and along the forend did not show up as normal until the golden age after war, when the demand for rifles plummeted (no more war) and gunsmiths had to do something special to make their pieces stand out and sell.

Ӣ Early longrifles either had no patchbox or had a sliding wooden patchbox prior to the war. Simple brass patch boxes came out right before the start of the war and progressively became more ornamental. Sliding wooden patchboxes were still common in the early war. "Daisy" pattern patchboxes were seen during the war, but "pierced" patchboxes didn't appear until after the war. Pierced patchboxes are those that have wood showing through the brass patchboxes as part of an ornamental pattern instead of the patchbox being solid brass in whatever shape was used.

Ӣ The wrist of the longrifle was always significantly wider than it was tall to make sure there was plenty of strength in the wrist to withstand the heavy loads needed for 50 to 62 caliber round balls. Wrists thinned out some after the war as caliber size went down and powder charges reduced accordingly. However, they never became narrow and tall as you often find now in production rifles.

Ӣ All of the original longrifles I've seen had very slender forends. The front stock was not very deep. That is perhaps a fine point, but most of the production longrifles have very thick fore-ends and you could easily take half the wood off the forend to get them closer to what they should be.

”¢ Rifle barrels varied in length with Haynes Lancaster rifles being short at 38" while more of them were 42 to 44½" in length. So plenty of room to play with there. Capt. John Warner of the Green Mountain Rangers had an exceptionally long rifle at 7-ft. in length. He used it at the Battle of Bennington. That was an unusual rifle. So basically any barrel from 38" to 44½" in length would definitely fall into the Rev War period.

Ӣ All barrels until the 1820's were hammer forge-welded and were swamped barrels. Straight and tapered barrels didn't appear until automatic machinery began making barrels (I believe that was the 1820's...not sure). A swamped barrel is night and day easier to mount, sight, hold on target, and just all around handle than a straight or tapered octagon barrel. I have both and there is absolutely no comparison in my opinion. Nonetheless, no one will give you pause if you don't have a swamped barrel. They are typically an extra $100 to $150 over the standard barrels and worth every penny of it.

Ӣ Barrels at the time were either finished "in the white", or were charcoal blued, which was a high-heat blued finish. The natural "in the white" barrels developed a natural patina with use, but are nowhere near being a "browned" barrel. Browning barrels didn't become popular until after the war. A blued barrel, bright barrel, or natural patina barrel would be typical but again, no one is going to give you grief if yours is browned.

Ӣ Early locks were either German or British as the colonists were prohibited from manufacturing locks. That doesn't mean we didn't do make them, but we tried not to get caught doing so. British locks came in by the barrel-full and were commonly and widely used prior to the war. If Mike Brooks pipes in, he can give you a lot more info about locks used from 1775-1783.

Ӣ Triggers can be either single trigger or double trigger (set trigger) designs as both were used during the war.

So there's some general guidelines to help you out. The rifle I use is an early Lancaster made by "tg" from here on the forum. With its Queen Anne lock (originally made from about 1720-1760) would be considered an early longrifle, pre-war. By the way, did I tell you what a beautiful job he did on it? I use it mostly for Rev War Reenactments, but hunt with it too. It draws admiring comments at almost every event I attend.

Anyway, hope this helps.

Twisted_1in66 :thumbsup: