Can anyone tell me if there is really a difference from a shooting standpoint from a hand forged wrought iron barrel and a modern barrel? Although price is a major factor, authenticity would say that hand forged is the only true authentic barrel. Can anyone tell, once the rifle is assembled, that the barrel is hand made or not? Also, is there any ballistic advantages to the hand forged barrel? Any advantages when it comes to cleaning the barrel after the shoot? I have heard that a seasoned wrought iron barrel is similar to a well seasoned wrought iron skillet that never sticks to food. Real? Thanks.

-

Friends, our 2nd Amendment rights are always under attack and the NRA has been a constant for decades in helping fight that fight.

We have partnered with the NRA to offer you a discount on membership and Muzzleloading Forum gets a small percentage too of each membership, so you are supporting both the NRA and us.

Use this link to sign up please; https://membership.nra.org/recruiters/join/XR045103

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

forged barrel vs machined

- Thread starter lthome5

- Start date

Help Support Muzzleloading Forum:

This site may earn a commission from merchant affiliate

links, including eBay, Amazon, and others.

Modern "machined" barrels are going to be supperior to any hand forged barrel. The current method is to drill the bore and then machine or grind the flats, leaving the bore true to center. It is almost imposible to have a forged barrel with the bore centered. The old timers had to make adjustment in the sights to compenste for the offset of the off-centered barrel.

As far a seasoning, cast iron does season easier, but higher carbon steels used today are still microscopically porous and can be seasoned.

I would not trust a heavy charge of powder in anything hand forged. It may be well made, but you never know.

Unless I wanted a damascus barrel, would not want hand forged.

As far a seasoning, cast iron does season easier, but higher carbon steels used today are still microscopically porous and can be seasoned.

I would not trust a heavy charge of powder in anything hand forged. It may be well made, but you never know.

Unless I wanted a damascus barrel, would not want hand forged.

The additional $4,000 to $8,000 usually is enough to scare away the general public. Any advantage would be short lived as the iron would wear down faster and need freshening. Most likely the modern high-end machined barrels are far and away more accurate than a hand forged barrel anyway. Accuracy is derived from consistancy.

paulvallandigham

Passed On

- Joined

- Jan 9, 2006

- Messages

- 17,537

- Reaction score

- 89

You can season iron. You can't season steel. What pores you may find in steel are not going to be large enough to accept the burned grease that seasons a cast iron skillet, for instance.

It is next to impossible to get true wrought Iron today. Its not being made any more and hasn't for years. What wrought Iron we do have is being recycled from old fences, some bridges, and other salvaged sources of the product. For a Muzzle loading rifle, shooting PRB, I can see No advantage to making a forged Wroght Iron Barrel.

Now, there are German barrel makers that use powered hammers to forge barrels around a mandrill, and those modern steel barrels are among some of the most accurate barrels made today. But, the equipment is expensive to do this, and there are cheaper ways to make fine, accurate barrels being used right here in the USA.

If Hammer forged barrels provided better accuracy than those that are made with button rifling, you would see them being used on .50 caliber sniper rifles and other rifles where the highest accuracy is needed for the work to be done.

I don't recall a hammer forged barrel winning the Wimbleton Cup match( 1,000 yds.) at Camp Perry, for instance. Nor do you see such barrels winning the major competitions for BP shooters, both RB, and conicals, at NMLRA Shoots held at Friendship( including the slug gun events shot at 800, 900, and 1,000 yds).

It is next to impossible to get true wrought Iron today. Its not being made any more and hasn't for years. What wrought Iron we do have is being recycled from old fences, some bridges, and other salvaged sources of the product. For a Muzzle loading rifle, shooting PRB, I can see No advantage to making a forged Wroght Iron Barrel.

Now, there are German barrel makers that use powered hammers to forge barrels around a mandrill, and those modern steel barrels are among some of the most accurate barrels made today. But, the equipment is expensive to do this, and there are cheaper ways to make fine, accurate barrels being used right here in the USA.

If Hammer forged barrels provided better accuracy than those that are made with button rifling, you would see them being used on .50 caliber sniper rifles and other rifles where the highest accuracy is needed for the work to be done.

I don't recall a hammer forged barrel winning the Wimbleton Cup match( 1,000 yds.) at Camp Perry, for instance. Nor do you see such barrels winning the major competitions for BP shooters, both RB, and conicals, at NMLRA Shoots held at Friendship( including the slug gun events shot at 800, 900, and 1,000 yds).

The old original iron barrels were very,very soft. That is why they had a large mass in the breech area. The flats were cut to even with a standard Draw Knife same one used to cut wood. These rifles came with a Freshing Tool so you could do a recut after a few hundred rounds. I can't imagine anyone wanting to blow there face off when you can get a good 4140 steel barrel. :thumbsup:

barrel.

barrel.

Most ML barrels are made of cold rolled steel because it machines easily.

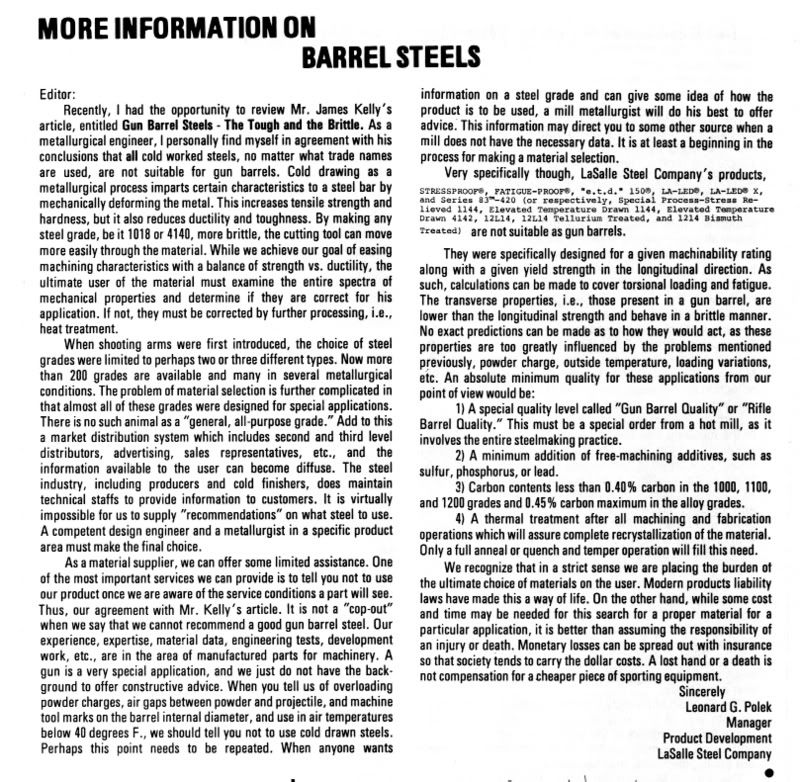

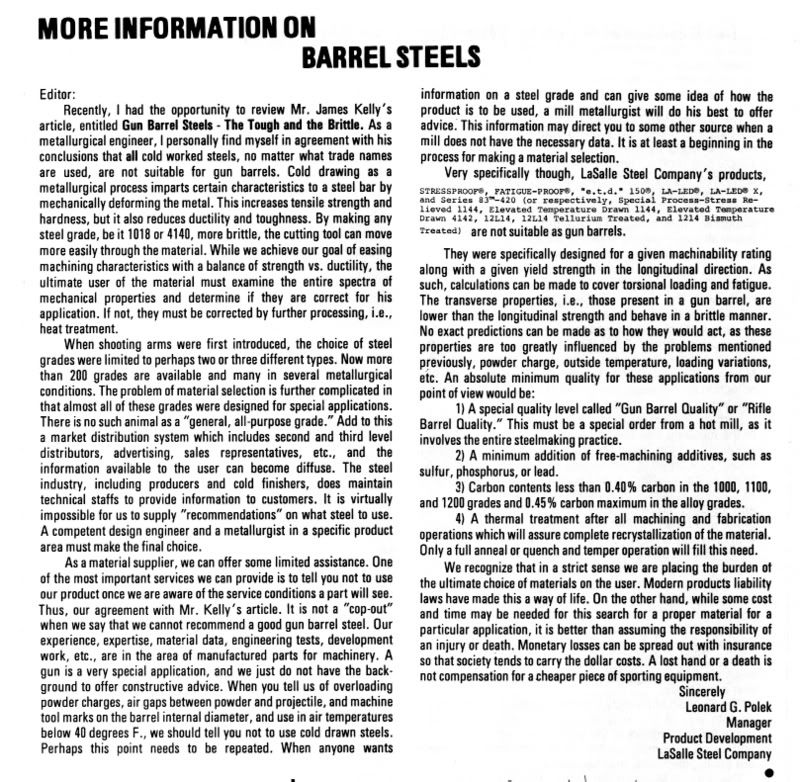

This will start a discussion I am sure, but below is a clip from pg 11 of the Nov 1981 Buckskin Report. It was sent to John Baird during a barrel steel discussion at that time.

Note that I did not write it. So don't argue with me, if you have issues with the contents contact the steel maker.

Dan

This will start a discussion I am sure, but below is a clip from pg 11 of the Nov 1981 Buckskin Report. It was sent to John Baird during a barrel steel discussion at that time.

Note that I did not write it. So don't argue with me, if you have issues with the contents contact the steel maker.

Dan

redwing said:The old original iron barrels were very,very soft. That is why they had a large mass in the breech area. The flats were cut to even with a standard Draw Knife same one used to cut wood. These rifles came with a Freshing Tool so you could do a recut after a few hundred rounds. I can't imagine anyone wanting to blow there face off when you can get a good 4140 steel barrel. :thumbsup:

barrel.

They were filed or ground actually. Many steels can be cut with a sharp tool.

Soft is not necessarily bad in a gun barrel.

The Springfield Rifle Musket barrel of the ACW was a skelp welded iron barrel. It was then run through a series or rollers to lengthen it and bring closer the finish size before being bored and rifled.

Dan

Mike Brooks

Cannon

- Joined

- Jul 19, 2005

- Messages

- 6,686

- Reaction score

- 33

The old timers actually bent the barrel till it shot where they wanted it to. If you look at any or all old rifles the sights are always on center.The old timers had to make adjustment in the sights to compenste for the offset of the off-centered barrel.

Mike Brooks

Cannon

- Joined

- Jul 19, 2005

- Messages

- 6,686

- Reaction score

- 33

Have you actually tried to shape an old barrel with a draw knife? Soft yes, but not that soft.The flats were cut to even with a standard Draw Knife same one used to cut wood. These rifles came with a Freshing Tool so you could do a recut after a few hundred rounds

First I have ever hear of a freshening tool being sold with a rifle. I have had several rifles with wrought iron barrels come through here recently, one had a Damascus rifled barrel. neither on showed signs of being refreshed and the bores were minty. They were being shot in the 50's and 60's at Friendship before modern made muzzleloaders were commonly available.

Mike Brooks said:The old timers actually bent the barrel till it shot where they wanted it to. If you look at any or all old rifles the sights are always on center.The old timers had to make adjustment in the sights to compenste for the offset of the off-centered barrel.

I dissagree.

The barrel was placed in the stock with the off-set of the bore to the top or the bottom, never to the side. That is why the sights were centered.

Walter Cline made a habit of reboring, rerifling and freshing barrels according to his book. Just about every rifle barrel he got his hands on was reworked it seemed.

Damascus if "hard" withstood wear better than iron according to Forsythe.

Dan

Damascus if "hard" withstood wear better than iron according to Forsythe.

Dan

Real wrought iron is still available but is a little on the pricey side.

http://www.realwroughtiron.com/

Last edited by a moderator:

muzzledoc said:Can anyone tell me if there is really a difference from a shooting standpoint from a hand forged wrought iron barrel and a modern barrel? Although price is a major factor, authenticity would say that hand forged is the only true authentic barrel. Can anyone tell, once the rifle is assembled, that the barrel is hand made or not? Also, is there any ballistic advantages to the hand forged barrel? Any advantages when it comes to cleaning the barrel after the shoot? I have heard that a seasoned wrought iron barrel is similar to a well seasoned wrought iron skillet that never sticks to food. Real? Thanks.

Seasoning barrels is complete BS. There is or was a "patch lube" on the market that used to build up in the bore. It would eventually adversely effect accuracy and was very hard to get out again. Many barrels shooting a PRB will smooth up in the first 50-100 shots and shoot much better as a result. This can be speeded up, if necessary, by lapping or working the bore with a tight wad of steel wool. This "breakin" period may be what makes some shooters think the barrel is "seasoned" as the accuracy improves.

This is too complex for the time I want to spend but here goes.

There are basically two things that effect accuracy. Careful workmanship and uniform material.

One must be very careful when thinking that new made barrels are superior to old barrels in accuracy or anything else. Welded iron barrels were used in very large numbers in America until the coming of the cartridge era. Iron barrels, *properly made* are capable of very fine accuracy. But many had very poor rifling forms that might not produce the accuracy that a barrel made today with wider grooves and a more stable rifling guide will. But there is no way would I state that any given steel barrel would out shoot any give iron barrel.

But the earlier the barrels are the lower the quality may be. Trade gun barrels were notoriously bad. This continued into at least the 1830s according to W Greener.

American rifles in the 18th century at least were made with both import and American made barrels. Barrel making was an early industry. I suspect the quality of material varied in all of them. Imported barrels or barrel blanks were being used in America till at least the dawn of the 20th century. Parker shotguns used best quality British Damascus for example. Damascus being a mix of different alloys iron and steel welded together to form a pattern.

The *best quality* machine made British Damascus steel was equal to "Whitworth steel" as a barrel material and many British shotguns with welded damascus barrels carry nitro proofs and are still in use or are still being proved for use. So welding in itself is not a indicator of strength when compared to mild steel.

To explain actual strength in gun barrels (as opposed to the tensile and yield number for the material which can be very misleading) requires more writing than I am willing to do right now.

Most don't want to here it anyway.

Dan

paulvallandigham

Passed On

- Joined

- Jan 9, 2006

- Messages

- 17,537

- Reaction score

- 89

I said that wrought iron is available, but its my understanding that the mills are using old wrought iron and reforming ( heating, melting, etc.) the old stuff to make new products. No one is making wrought iron from scratch any more.

Note your cited company's advertising at the bottom of the page for any old scrap iron.

Note your cited company's advertising at the bottom of the page for any old scrap iron.

I shoot a few original rifles. The bores seem to be very good in them and they shoot well. But, the metal is more porus then the new steel barrels. Cleaning can sometimes be a little test to make sure they are totally dry and when you lube the barrel after you think it is clean, you don't seal water into those pores. Yes, my barrels may have some pits in them, so that may be the problem as well. But, one barrel has been rebored and rifled and it has the same problem as well. I know the bore well, as I was the one that sent it in to have it done. I also tried the seasoning idea years ago. Though I think the lube is fine to use, do not buy into the seasoning idea. It will seal them pores as well and it maybe seaing your cleaning solutions in them pores. I doubt though with the usual proper care and with a bore guide, you will wear out a cast iron barrel in your lifetime. I know the one gun has survived many lifetimes already, on what I assume is it's original bore.

octagon said:Does anyone know if Rice and DeHass barrels are forged or machined steel?

Both are machined.

Dave K said:I shoot a few original rifles. The bores seem to be very good in them and they shoot well. But, the metal is more porus then the new steel barrels. Cleaning can sometimes be a little test to make sure they are totally dry and when you lube the barrel after you think it is clean, you don't seal water into those pores. Yes, my barrels may have some pits in them, so that may be the problem as well. But, one barrel has been rebored and rifled and it has the same problem as well. I know the bore well, as I was the one that sent it in to have it done. I also tried the seasoning idea years ago. Though I think the lube is fine to use, do not buy into the seasoning idea. It will seal them pores as well and it maybe seaing your cleaning solutions in them pores. I doubt though with the usual proper care and with a bore guide, you will wear out a cast iron barrel in your lifetime. I know the one gun has survived many lifetimes already, on what I assume is it's original bore.

Iron rifle barrels are not made of cast iron.

Nor are "cast steel" barrels cast as we might think.

It was a term for the process of how the steel was made not how the barrels were made from it.

Porous iron simply has a lot of inclusions in it I would guess.

In trying to weld up old Sharps receivers for repair the amount of silica and other slag in iron forgings from the mid-1800s becomes pretty apparent. But quality iron for barrels was worked more and the more it was heated and hammered and worked the cleaner it got.

Old horse shoe nails were the preferred material for quality barrels in England at one time. By the time the "stubs" were remelted and hammered into a bar it was pretty well cleaned.

See "The Gun" by W. Greener 1832 (this is not the much younger W.W.) for a description of the process.

Dan

ohio ramrod

75 Cal.

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2008

- Messages

- 7,473

- Reaction score

- 2,209

Actually unless they stopped in the last few years there is a mill in England still making true wrought iron. But it is costly and you need to order at least 1000 lb.I haven't done any forging work for the last five years so I don't know for sure if they are still running but I assume they are. For what it is worth, it is my understanding that the soft iron barrels do have a "dampning" quality that accounts for why the origional Rigby rifles were winning matches for such a long period of time.

Tumblernotch

69 Cal.

- Joined

- Feb 26, 2005

- Messages

- 3,370

- Reaction score

- 11

Dan Phariss said:Dave K said:I shoot a few original rifles. The bores seem to be very good in them and they shoot well. But, the metal is more porus then the new steel barrels. Cleaning can sometimes be a little test to make sure they are totally dry and when you lube the barrel after you think it is clean, you don't seal water into those pores. Yes, my barrels may have some pits in them, so that may be the problem as well. But, one barrel has been rebored and rifled and it has the same problem as well. I know the bore well, as I was the one that sent it in to have it done. I also tried the seasoning idea years ago. Though I think the lube is fine to use, do not buy into the seasoning idea. It will seal them pores as well and it maybe seaing your cleaning solutions in them pores. I doubt though with the usual proper care and with a bore guide, you will wear out a cast iron barrel in your lifetime. I know the one gun has survived many lifetimes already, on what I assume is it's original bore.

Iron rifle barrels are not made of cast iron.

Nor are "cast steel" barrels cast as we might think.

It was a term for the process of how the steel was made not how the barrels were made from it.

Porous iron simply has a lot of inclusions in it I would guess.

In trying to weld up old Sharps receivers for repair the amount of silica and other slag in iron forgings from the mid-1800s becomes pretty apparent. But quality iron for barrels was worked more and the more it was heated and hammered and worked the cleaner it got.

Old horse shoe nails were the preferred material for quality barrels in England at one time. By the time the "stubs" were remelted and hammered into a bar it was pretty well cleaned.

See "The Gun" by W. Greener 1832 (this is not the much younger W.W.) for a description of the process.

Dan

Right you are, Dan. A lot of people here are confusing wrought iron with cast iron, especially when talking about "seasoning" barrels. But that horse has been flogged to death on a few other threads and I won't get into it here. Wrought iron, especially that made here in the States, does have slag inclusions in it and that, besides poor welding, has caused most of the barrel failures through history. A look in the records of the Harpers Ferry Armory shows a period when the armory was receiving very poor grade skelps from a certain Pennsylvania ironworks and was experiencing a catastrophic failure rate when the barrels were going through their first proof. And many which had passed the first were failing after final reaming and polishing of the bores.

I took a notion recently of forging a pistol barrel out of some old wrought iron strap I have in the shop. It was big enough to make a skelp from and I took a sample piece and heated it in the forge at near welding heat and drew it out a little before doing a bending test. It immediately started splitting and "brooming out". To make it fit for anything, it would have to be hammered, folded and re-welded many times and even then may not work. From what I've seen here as well as other pieces I've forged, not to mention some study about American wrought iron, most of the scrap wrought iron one finds is too full of slag to be safely used for gun barrels.

Most of the barrels used by Springfield Armory during the Civil War was Marshall iron and it did have the qualities to make a premium barrel. However, like the English iron imported during the War, there were bad lots that slipped through. According to several blacksmith/steel maker writers that I've had the opportunity to read, Swedish or Norway iron was the best up until this past century, though I know some good quality iron was made here. (I'd have to look up the makers). The problem is, who made that skelp that you're holding in your hand getting ready to make a barrel out of? I've heard that good Swedish iron mined from the bed of a lake there was still available until a few years ago at least. I haven't checked lately.

I'm no metallurgist so I can't give a bunch of figures and all that stuff to explain the wherefores and hows without quoting from the several books I have that treat with wrought iron. I do know that it is more fibrous than crystalline in nature, much like the fibers in wood. One interesting thing that I have found in my studies on Civil War guns was the fact that Cook and Brother who made a fine copy of the Enfield for the Confederacy, twisted the stock used for their barrels while hot to lay the inclusions at right angles to the axis of the bore. This supposedly made the barrels stronger by not having long seams formed by inclusions running in line with the bore. The Cooks also drilled their barrels from solid bars rather than welding them from skelps. One writer says that they used Swedish iron, but I doubt that seriously considering it was supposed to be high quality and the difficulty of getting it through the blockade. A look at a Cook rifle barrel will show the inclusions running in a spiral around the barrel. I've got a short piece of wrought iron in my shop that I had turned down a few years ago to see how it looked inside. The outside was quite eroded (this stuff doesn't rust the same as mild steel, in fact it generally lasts longer). I turned it down in steps and found that most inclusions are quite shallow and probably wouldn't be a major factor in a barrel failure unless at a thin place or under a very heavy load. If twisted, they may become stronger I suppose, but on the other hand, twisting could cause further separation and weakening. If I was to ever take the plunge and forge a barrel from wrought iron, I would play it safe and have it X-rayed or magnafluxed and then I would proof it twice and re-X-rayed before trusting it fully. And I would never use a load heavier than what should be used in whatever caliber it was.

Mention was made earlier of using a drawknife to cut the flats on a barrel. I have read in at least two different sources that some iron was soft enough to do it. I've never seen such iron, but I'm not going to say it couldn't have been done...yet.

Sorry for the long epistle, but ya'll know me. :yakyak:

Similar threads

- Replies

- 7

- Views

- 538

- Replies

- 22

- Views

- 2K

- Locked

- Replies

- 4

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 95

- Views

- 3K

Latest posts

-

-

FOR SALE very nice Veteran Arms 1st Land Pattern Brown Bess for sale!

- Latest: FlintlockMilitaryRifle

-

-

-

-

-

-