- Joined

- Nov 26, 2005

- Messages

- 5,224

- Reaction score

- 10,884

Hi,

I originally posted this in a thread started by Brokennock but I thought it would be better to continue the saga in a separate thread. I am repeating some of what I already wrote and will be adding a lot of new material soon. The purpose of this thread is not to document another project but to show you how I do some of the hard stuff that nobody else posts such as, intricate wire inlay, intricate inlays, engraving, and wood carving. I am not going to discuss basics. You can get that from other threads and tutorials, books, CDs, and on You Tube if you are careful. I will also eventually post this on the ALR site as well.

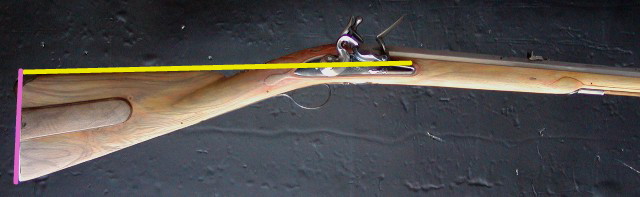

This is a project I wanted to get to for a long time but always something else got in the way. I finally decided to just do it despite my queue of other work. I am restocking a mid-18th century English rifle that I built some years ago and was never happy with (shown below).

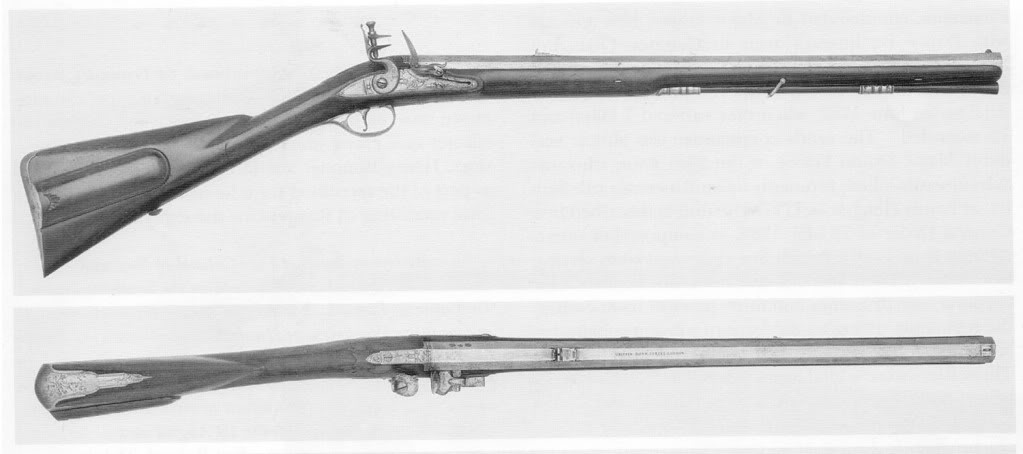

The stock had way too much drop. I copied an original rifle (pictured below)

thinking it would fit well but after pairing down the stock it was apparent the drop at heel was too much and my cheek could never get a solid position on the stock. I was able to shoot it fairly well but I was disappointed in my choice. I had made a mistake. So, I am restocking it using a different design more closely inspired by the famous Turvey rifle in RCA #1. This gun will be a pleasure to shoot. It is difficult to make these early 18th century English rifles because the British did not make many and there are very few that have survived. In fact, I am aware of more early to mid 18th-century English rifles that are breech loading screw plug deer park rifles than more traditional muzzle loading designs. There are plenty of late 18th and early 19th century English rifles for study but they differ a lot from those made earlier in the century.

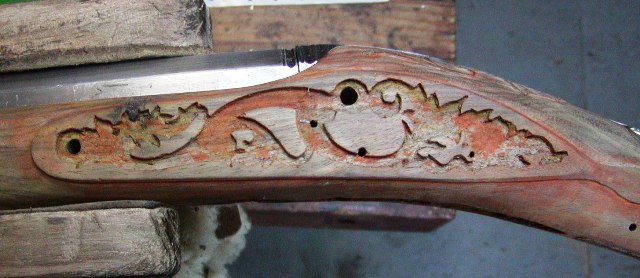

My rifle uses a 31" Rice Jaeger barrel in 62 caliber, a Chambers round-faced English lock, a "Dubbs" longrifle butt plate heavily modified by filing and welding, a modified steel early husk trigger guard from Chambers, steel pipes, and rear folding leaf Jaeger sight. The rifle uses barrel keys and a hook tang and breech modified from one that used to be sold by TOW for 1 1/8" barrels. It required shaping the tang and adding a proper cross pin lug on the bottom of the standing breech to match the originals. Pretty much everything else is hand made. The lock plate was shortened by 1/4" and angled slightly down to the rear to get the wrist architecture right. I wish that Chambers lock was 5 5/8" long rather than 6" because it would be far more versatile. The stock is English walnut that I bought from Dave Rase. It was originally full fowler length and inlet by Dave for a 44" octagon/round fowler barrel. However, it had some problems. After sitting in my shop for a year it developed a horrendous twist and warp as well as a crack in the butt stock. It also had some old powder post beetle holes and a couple of poorly positioned knots. Nonetheless, they were nothing I could not fix so I chose to use it for a short rifle instead, which solved the twist and warp issue and cracks, knots, and beetle holes were either cut away or stabilized, strengthened, and filled with Acra Glas. The yellow and orange colors you see are from water-based stains I use during whiskering that reveal scratches and rough spots more readily. None of the old color will remain when I am ready to stain the stock with alkanet root.

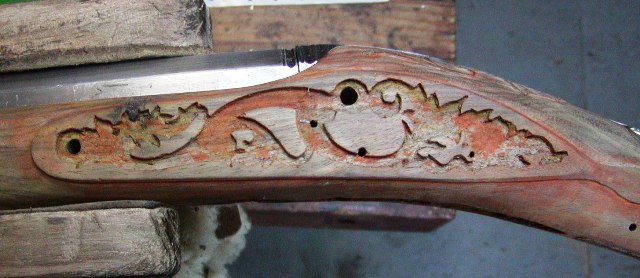

This rifle has some intricate inlays and silver wire work. I will show how those inlays were made and finished.

I will show how those intricate inlays were made and inlet and how I did the complex silver wire work. I will also so how I carved the stock. Throughout all I will discuss the historical context and designs.

dave

I originally posted this in a thread started by Brokennock but I thought it would be better to continue the saga in a separate thread. I am repeating some of what I already wrote and will be adding a lot of new material soon. The purpose of this thread is not to document another project but to show you how I do some of the hard stuff that nobody else posts such as, intricate wire inlay, intricate inlays, engraving, and wood carving. I am not going to discuss basics. You can get that from other threads and tutorials, books, CDs, and on You Tube if you are careful. I will also eventually post this on the ALR site as well.

This is a project I wanted to get to for a long time but always something else got in the way. I finally decided to just do it despite my queue of other work. I am restocking a mid-18th century English rifle that I built some years ago and was never happy with (shown below).

The stock had way too much drop. I copied an original rifle (pictured below)

thinking it would fit well but after pairing down the stock it was apparent the drop at heel was too much and my cheek could never get a solid position on the stock. I was able to shoot it fairly well but I was disappointed in my choice. I had made a mistake. So, I am restocking it using a different design more closely inspired by the famous Turvey rifle in RCA #1. This gun will be a pleasure to shoot. It is difficult to make these early 18th century English rifles because the British did not make many and there are very few that have survived. In fact, I am aware of more early to mid 18th-century English rifles that are breech loading screw plug deer park rifles than more traditional muzzle loading designs. There are plenty of late 18th and early 19th century English rifles for study but they differ a lot from those made earlier in the century.

My rifle uses a 31" Rice Jaeger barrel in 62 caliber, a Chambers round-faced English lock, a "Dubbs" longrifle butt plate heavily modified by filing and welding, a modified steel early husk trigger guard from Chambers, steel pipes, and rear folding leaf Jaeger sight. The rifle uses barrel keys and a hook tang and breech modified from one that used to be sold by TOW for 1 1/8" barrels. It required shaping the tang and adding a proper cross pin lug on the bottom of the standing breech to match the originals. Pretty much everything else is hand made. The lock plate was shortened by 1/4" and angled slightly down to the rear to get the wrist architecture right. I wish that Chambers lock was 5 5/8" long rather than 6" because it would be far more versatile. The stock is English walnut that I bought from Dave Rase. It was originally full fowler length and inlet by Dave for a 44" octagon/round fowler barrel. However, it had some problems. After sitting in my shop for a year it developed a horrendous twist and warp as well as a crack in the butt stock. It also had some old powder post beetle holes and a couple of poorly positioned knots. Nonetheless, they were nothing I could not fix so I chose to use it for a short rifle instead, which solved the twist and warp issue and cracks, knots, and beetle holes were either cut away or stabilized, strengthened, and filled with Acra Glas. The yellow and orange colors you see are from water-based stains I use during whiskering that reveal scratches and rough spots more readily. None of the old color will remain when I am ready to stain the stock with alkanet root.

This rifle has some intricate inlays and silver wire work. I will show how those inlays were made and finished.

I will show how those intricate inlays were made and inlet and how I did the complex silver wire work. I will also so how I carved the stock. Throughout all I will discuss the historical context and designs.

dave