- Joined

- Nov 26, 2005

- Messages

- 5,225

- Reaction score

- 10,887

Hi,

Robert Wogdon was so famous a maker of dueling pistols, he even had a poem written about him. These Wogdon dueling pistols arrived last Friday. For me, these are a Holy Grail of gun making. Disassembling and examining them is like taking a master class in gun making from one of the best ever. Over the next few days, I intend to post a lot of photos of the pistols, inside and out, and discuss them in detail. But for now, I'll just post the eye candy.

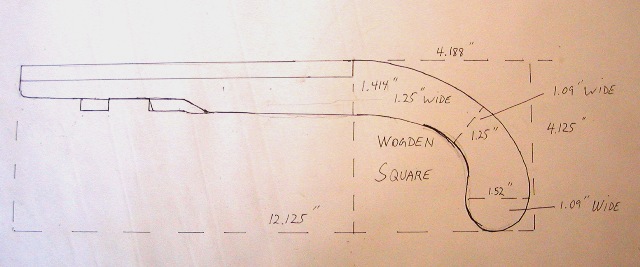

They are 40 bore (0.488 caliber) and are in very good condition. The flint **** on the pistol in the third photo above is a replacement and I will reshape it to match the other. Both pistols have some stock damage around the barrel keys nearest the muzzles and on one the stock is split at the muzzle, which I will repair. They are both in perfectly useable condition.

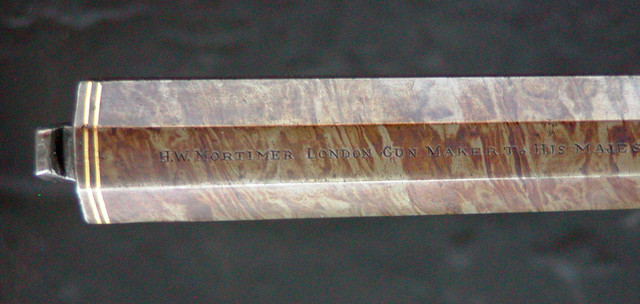

They can be dated very accurately. The London Gunmakers Guild view and proof marks are clear on the barrels. Wogdon used the private Tower proofing service until 1774 so these pistols are no earlier than that. Wogdon also shifted the location of his proof and makers marks to the underside of his barrels in 1778. Therefore, these pistols were definitely made between 1774 and 1778. The oval style of the rouletting engraved at the breech of the barrel and the acorn trigger guard finials also point to that time period.

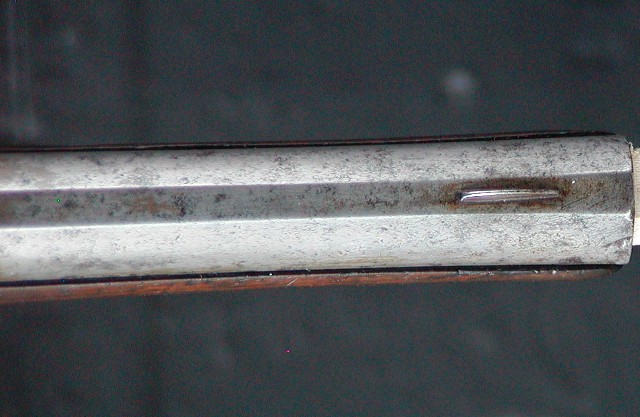

The barrels are of his "French" form. They have a slight octagon shape at the breech but are mostly round and taper toward the muzzle.

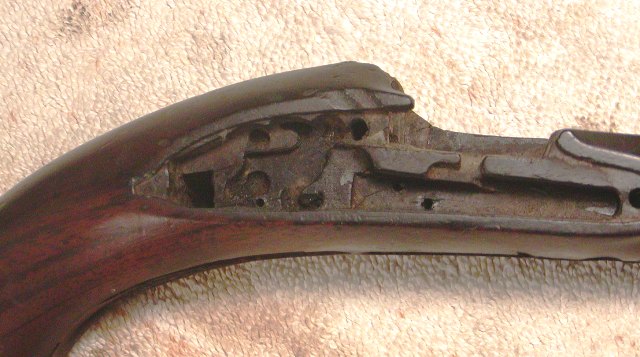

The locks are superb examples of the best lock making during the 1770s. They have safety bolts but do not yet have the "water proof" pans or frizzen roller bearings. Moreover, the pistols have simple triggers not the set or hair triggers common to dueling pistols 5-10 years later. These guns were made fairly early in Wogdon's long career.

In the next posts, I will discuss details about the locks, barrels, stocks, and hardware. In the process, hope to dispel a lot of rubbish considered common knowledge about dueling pistols both in literature and online. In addition, I will discuss how to make pistols like these. Enjoy the ride.

dave

Robert Wogdon was so famous a maker of dueling pistols, he even had a poem written about him. These Wogdon dueling pistols arrived last Friday. For me, these are a Holy Grail of gun making. Disassembling and examining them is like taking a master class in gun making from one of the best ever. Over the next few days, I intend to post a lot of photos of the pistols, inside and out, and discuss them in detail. But for now, I'll just post the eye candy.

They are 40 bore (0.488 caliber) and are in very good condition. The flint **** on the pistol in the third photo above is a replacement and I will reshape it to match the other. Both pistols have some stock damage around the barrel keys nearest the muzzles and on one the stock is split at the muzzle, which I will repair. They are both in perfectly useable condition.

They can be dated very accurately. The London Gunmakers Guild view and proof marks are clear on the barrels. Wogdon used the private Tower proofing service until 1774 so these pistols are no earlier than that. Wogdon also shifted the location of his proof and makers marks to the underside of his barrels in 1778. Therefore, these pistols were definitely made between 1774 and 1778. The oval style of the rouletting engraved at the breech of the barrel and the acorn trigger guard finials also point to that time period.

The barrels are of his "French" form. They have a slight octagon shape at the breech but are mostly round and taper toward the muzzle.

The locks are superb examples of the best lock making during the 1770s. They have safety bolts but do not yet have the "water proof" pans or frizzen roller bearings. Moreover, the pistols have simple triggers not the set or hair triggers common to dueling pistols 5-10 years later. These guns were made fairly early in Wogdon's long career.

In the next posts, I will discuss details about the locks, barrels, stocks, and hardware. In the process, hope to dispel a lot of rubbish considered common knowledge about dueling pistols both in literature and online. In addition, I will discuss how to make pistols like these. Enjoy the ride.

dave