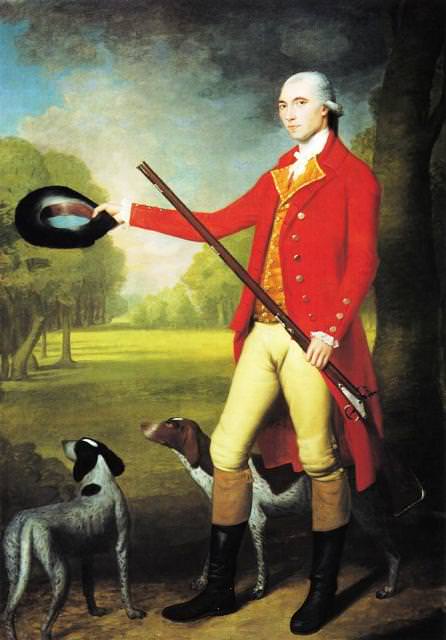

Pennsylvania style rifle?

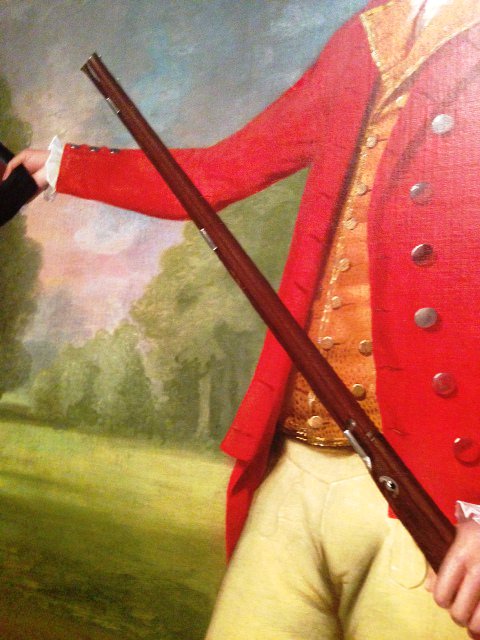

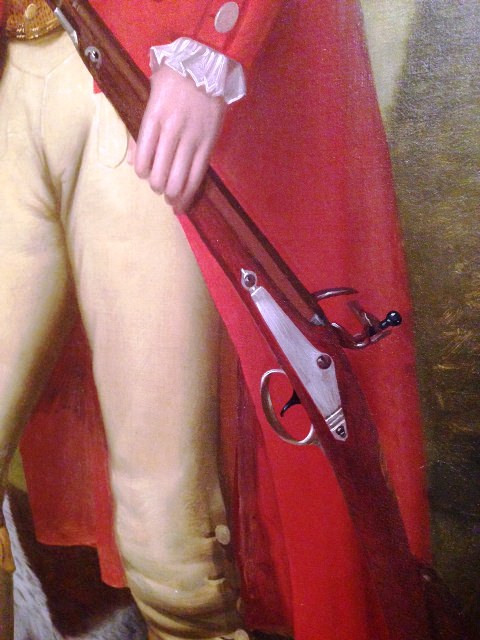

In the white? Or blue of some sort? Or either?

In the white? Or blue of some sort? Or either?

In fact, there is little evidence of rust browning on American long rifles until the 19th century.

Hi,

I am not aware of any evidence of Pennsylvania rifles with rust blued or browned barrels during the 1770s. There are a few examples that may have had charcoal or heat blued barrels. The locks were often case hardened but the fashion of preserving case colors rather than polishing them off is lacking. There also is no mention of rust browning or bluing chemicals in any surviving shop inventories from the 1770s. In fact, there is little evidence of rust browning on American long rifles until the 19th century.

dave

Angier said:In the literature on the subject the statement is generally found that the browning of gun barrels with this substance originated in England towards the end of the 18th century, which may be quite correct as regards military arms. The browning of barrels is in itself however much older, even in England, and according to information kindly given the author by Mr. C. E. Greener (the well-known Birmingham gunmaker), was in common use for sporting arms about 1720. A report of 1637 in the London Record Office explicitly mentions the "russetting" of barrels under the heading of "Repairs to the Arms of the Trained Bands" (London Militia).

Angier further said:A similar development took place at the same time on the European Continent: guns of the 18th century with blued (temper-blued) and browned barrels are numerous, and of the 17th century occasionally met with, in every larger public or private collection of firearms.

On American guns Angier said:Exactly the same advance took place on the American Continent, and the American backwoodsman, using the simplest possible means, browned the barrels of their historically famous, home-made rifles, from about the middle of the 18th century onwards [sic].

Hi Phil,

The problem is there is just no evidence on surviving guns. Folks can speculate all they want but if you ask what is historically correct, which by default means of what is there evidence or documentation, you fall flat. I am thoroughly familiar with Angier's book and he wrote long ago and was prone to misconceptions about historical gunmaking common to the era in which he wrote. He provides absolutely no documentation for the passage you cited. Much has been learned since.

dave

Trade Guns of the Hudson's Bay Company page 137 said:At a meeting of the Governor and Committee of the HBC held on December 20, 1780 it was...Ordered...That in future the Guns have Brown Stocks (no white) the Barrals [sic] likewise Brown with an additional Weight of 6 oz to them for Strength.

Gooding said:It must be remembered that the traders did not want a row of identical guns: better to give their customer a variety from which to make a selection. That variety could be as simple as the length of barrel, or a "Fine Gun" with a little extra brass.

That's probably why I enjoyed his book, he's writing on my level.Wm Cleator was a gentleman observer, not a gun maker and his description of the process has the vagueness of someone whose understanding is woefully superficial.

Enter your email address to join: