- Joined

- Nov 26, 2005

- Messages

- 5,223

- Reaction score

- 10,882

Hi folks,

I've been working on and off on a second Hawk New England fowler for a while. I am just catching up with posting so I put up some photos taken a while ago. The original Connecticut River Valley gun can be seen here:

https://americanlongrifles.org/forum/index.php?topic=49909.msg494966#msg494966

It is one of the finest New England fowlers ever made. I made a version of it several years ago:

https://americanlongrifles.org/forum/index.php?topic=52871.0

This time, I am making it closer to the original and included a longer barrel. The original has a 57" French barrel that is incredibly thin walled. I could not get that duplicated so I finally settled on a 20 gauge 50" barrel by FCI with the idea of working it over. It took me 2 years to find and get that long a barrel. It was made in the Spanish form and originally had a wedding band transition from octagon to round and a flare at the muzzle.

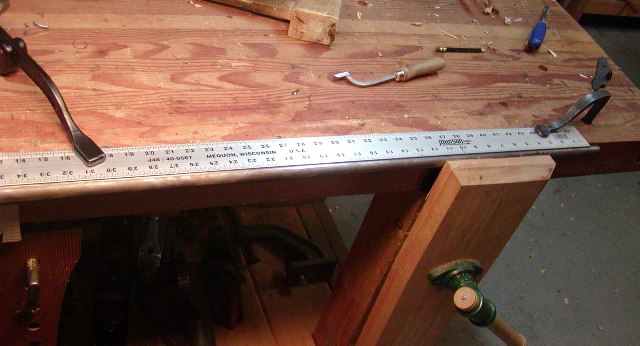

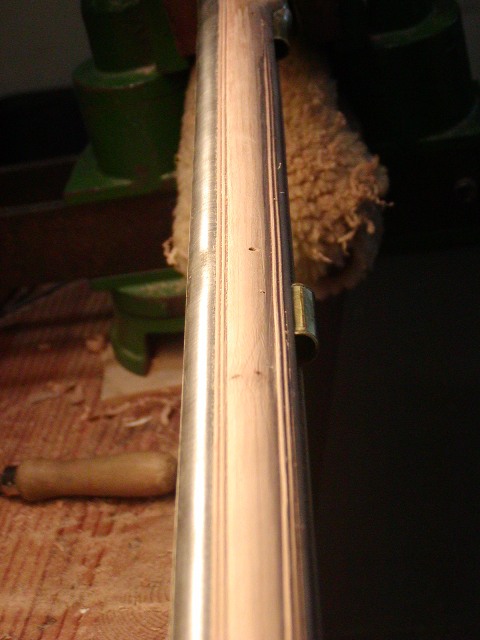

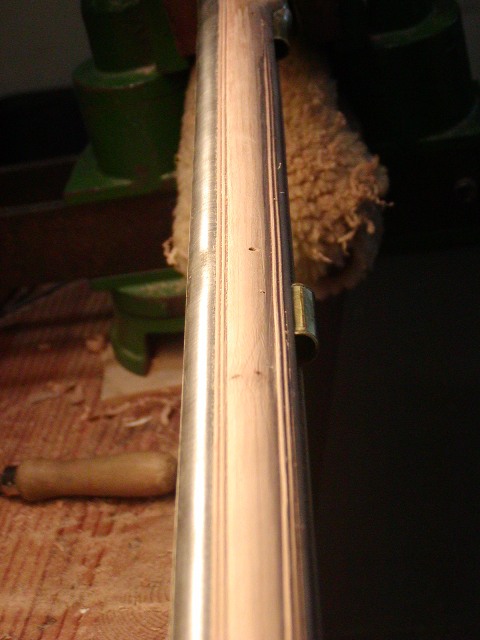

Both features had to go. I wanted a simple unadorned transition from octagon to round and no flare at the muzzle, just a slightly tapered tube all the way. Now some of you would advise taking it to a machine shop but I could do it on my own. My secret weapon is the 12" single cut razor sharp lathe file. In one and a half days of work, I got rid of the wedding band, tapered the octagon section the way I wanted, and got rid of the flare at the muzzle. In the process, the mound of steel wool shavings at my feet grew to 8-10" high. The barrel lost a pound of weight. The transitions machined in the barrel for the swamp and flare were abrupt and blobby. I wiped all of that roughness out. The next step was to cut the sight plane down the full lenght of the barrel.

This is how I did it.

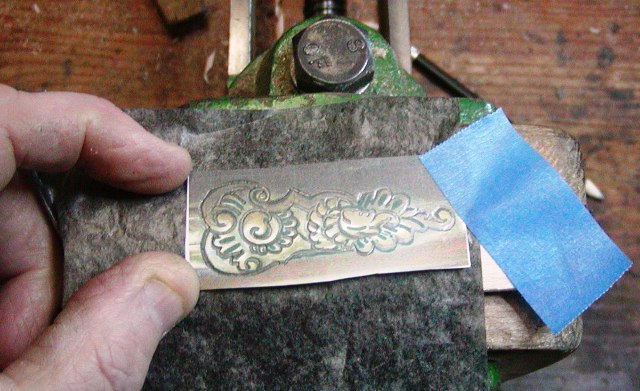

The silver front sight will be mortised into the barrel just in front of the end of the sight plane.

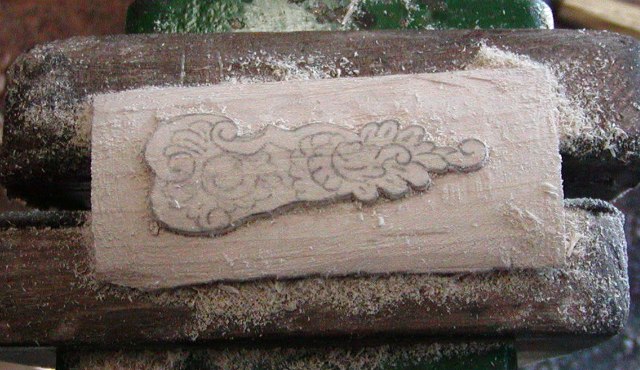

The stock is band sawed out of a dense cherry blank. Notice how tight and straight the grain is running through the wrist.

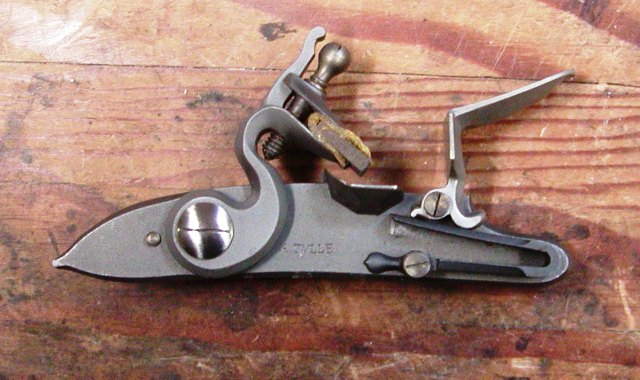

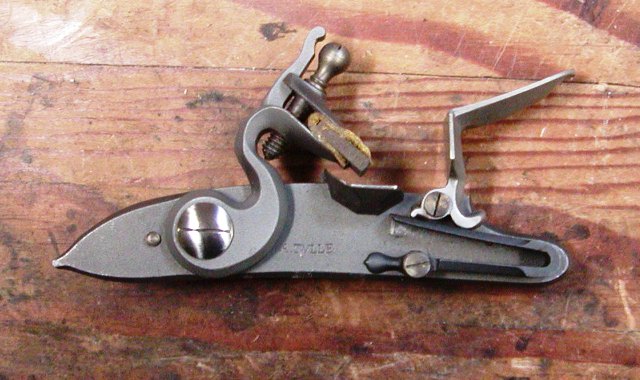

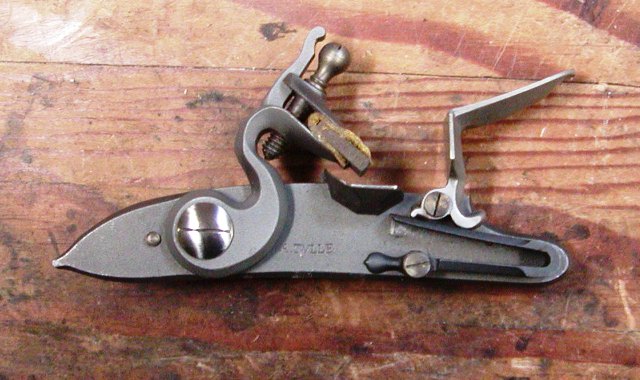

The lock will be a TOW Tulle lock because it has the best fit superficially to the original lock. Beyond that superficial appearance it is a piece of junk despite some saying "it is a good sparker". Let's look at it. Outside, with some welding, it will serve the purpose. Inside, it is a joke. Look at the position of the mainspring. It is so high on the plate that it could never be mated with an historically accurate large breeched barrel without the mainspring breaking into the barrel channel. This is stupid beyond belief. Also note that the hook of the mainspring just barely hits the toe of the tumbler at rest. Most importantly, look at the length of the lock plate bolster and how it does not overlap the shoulder on the flint ****. So the shoulder of the **** rest against the thinner edge of the lock plate just barely. Now imagine inletting that such that the shoulder of the **** clears the stock. It is very close to exposing a gap behind the lock plate. This is so stupid and if the bolster was extended just 1/8" more, the problem would be solved. Well of course that is what I will do as well as many other things.

More to come.

dave

I've been working on and off on a second Hawk New England fowler for a while. I am just catching up with posting so I put up some photos taken a while ago. The original Connecticut River Valley gun can be seen here:

https://americanlongrifles.org/forum/index.php?topic=49909.msg494966#msg494966

It is one of the finest New England fowlers ever made. I made a version of it several years ago:

https://americanlongrifles.org/forum/index.php?topic=52871.0

This time, I am making it closer to the original and included a longer barrel. The original has a 57" French barrel that is incredibly thin walled. I could not get that duplicated so I finally settled on a 20 gauge 50" barrel by FCI with the idea of working it over. It took me 2 years to find and get that long a barrel. It was made in the Spanish form and originally had a wedding band transition from octagon to round and a flare at the muzzle.

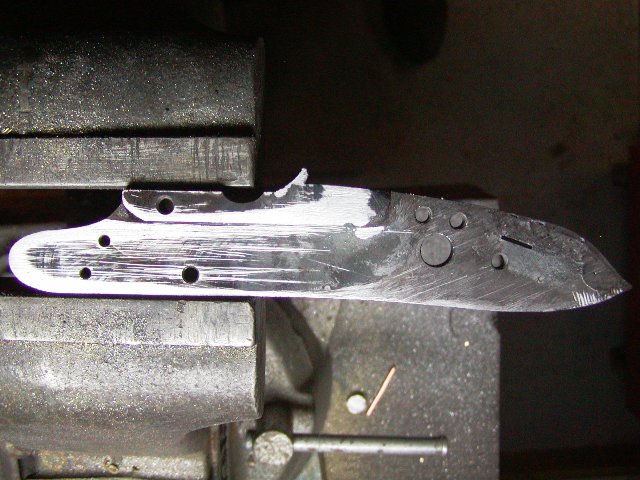

Both features had to go. I wanted a simple unadorned transition from octagon to round and no flare at the muzzle, just a slightly tapered tube all the way. Now some of you would advise taking it to a machine shop but I could do it on my own. My secret weapon is the 12" single cut razor sharp lathe file. In one and a half days of work, I got rid of the wedding band, tapered the octagon section the way I wanted, and got rid of the flare at the muzzle. In the process, the mound of steel wool shavings at my feet grew to 8-10" high. The barrel lost a pound of weight. The transitions machined in the barrel for the swamp and flare were abrupt and blobby. I wiped all of that roughness out. The next step was to cut the sight plane down the full lenght of the barrel.

This is how I did it.

The silver front sight will be mortised into the barrel just in front of the end of the sight plane.

The stock is band sawed out of a dense cherry blank. Notice how tight and straight the grain is running through the wrist.

The lock will be a TOW Tulle lock because it has the best fit superficially to the original lock. Beyond that superficial appearance it is a piece of junk despite some saying "it is a good sparker". Let's look at it. Outside, with some welding, it will serve the purpose. Inside, it is a joke. Look at the position of the mainspring. It is so high on the plate that it could never be mated with an historically accurate large breeched barrel without the mainspring breaking into the barrel channel. This is stupid beyond belief. Also note that the hook of the mainspring just barely hits the toe of the tumbler at rest. Most importantly, look at the length of the lock plate bolster and how it does not overlap the shoulder on the flint ****. So the shoulder of the **** rest against the thinner edge of the lock plate just barely. Now imagine inletting that such that the shoulder of the **** clears the stock. It is very close to exposing a gap behind the lock plate. This is so stupid and if the bolster was extended just 1/8" more, the problem would be solved. Well of course that is what I will do as well as many other things.

More to come.

dave