- Joined

- Nov 26, 2005

- Messages

- 5,229

- Reaction score

- 10,918

Hi,

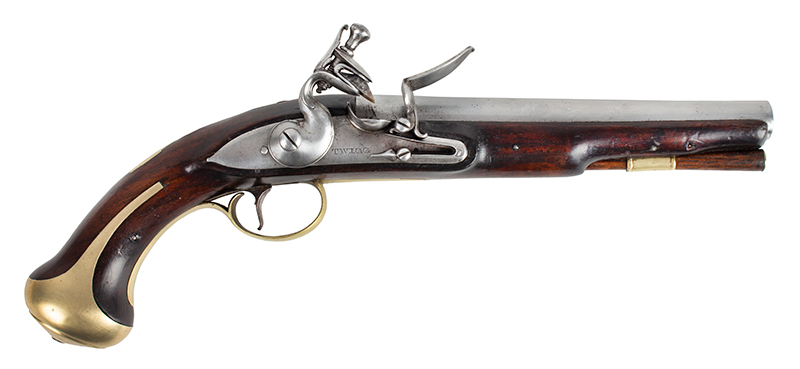

I am working on an early pattern Brown Bess and on a rifle for my blind friend, Josh. I am also starting a close copy of the Edward Marshall rifle but have to wait for delays in getting parts. While I wait, I thought I would build this pistol, which is a kit that was offered by the late Bill Kennedy. Bill was one of my mentors years ago and I jumped at the chance to make one of his kits, which are now very rare. I bought the kit from my friend, Dave Rase, out in Bremerton, Washington. Dave is a superb gun maker in his own right but he bought the kit years ago and never got to building it. The barrel was made by Bill and is 20 gauge, 8" long, and stamped with correct London proof marks and "WK" . I show it against a barrel from a long land Brown Bess. The precarved stock is English walnut and the hardware was cast by Bill in brass and is superb. The lock is Chambers small round-faced English lock, which is a very fine lock with a little work. It uses small Siler internals. I show it against an early Brown Bess lock for comparison.

So for me, the first question is, what am I going to make? What will the pistol represent? Unlike many, I care a lot about historical consistency. So I had to figure out what I had to work with. The pistol is mostly consistent with moderate quality pistols from the era. For example, it has the classic British acorn trigger guard. That became popular during the 1770s but by then, high quality pistols would have flat-faced locks. The round-faced lock was relegated to military, livery, and trade guns by that time. If the trigger guard was of an earlier style such that the pistol could credibly be from the 1750s, I could create a high-end gun. As it is, it needs to represent a less expensive gun from the 1770s and a private purchase officer's side arm is the historical ticket. So that is what it will be. It will represent a modest quality pistol purchased by an officer without the wealth to buy a higher grade. So what does that mean? It means I build it as is, I include a little carving around the barrel tang, and the engraving will be effective but not highest quality. There won't be a hook and tang breech nor high-end ribbed ramrod pipes and silver wire inlay. It will have the facade of quality without the details. Now at that time, that meant a very well made gun compared to American colonial production but without the frills associated with first quality London production.

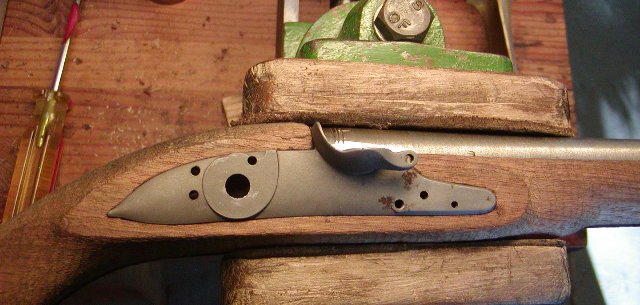

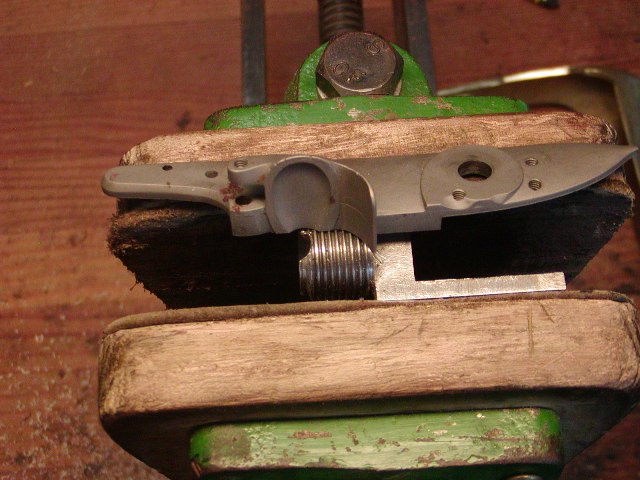

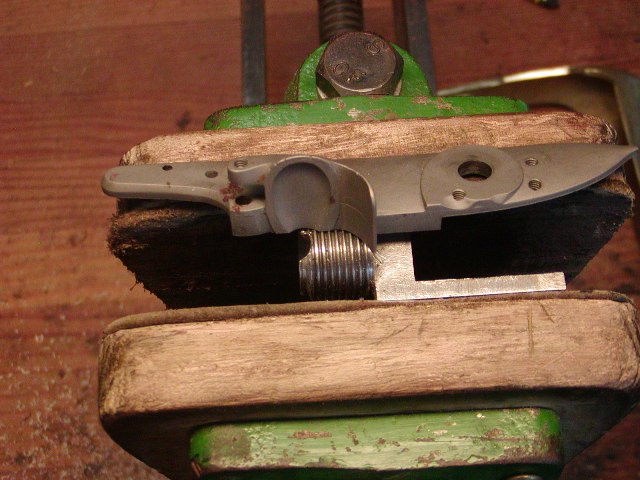

So here I go on another historical adventure. The first issue to resolve is the breech plug threads go really deep into the barrel. So deep, that there is no way I could position the lock in the precarved mortice to avoid the touch hole going right in to the breech plug. I did not want to move the barrel back because I want the fence of the lock to be correctly located at the end of the barrel. The solution was to hollow out the breech plug and notch it for the lock. It is really simple to do with drills and a drill press, and then grinders attached to a Dremel. It came out nicely and solves the problem. I will inlet the barrel tomorrow, so more is coming.

dave

I am working on an early pattern Brown Bess and on a rifle for my blind friend, Josh. I am also starting a close copy of the Edward Marshall rifle but have to wait for delays in getting parts. While I wait, I thought I would build this pistol, which is a kit that was offered by the late Bill Kennedy. Bill was one of my mentors years ago and I jumped at the chance to make one of his kits, which are now very rare. I bought the kit from my friend, Dave Rase, out in Bremerton, Washington. Dave is a superb gun maker in his own right but he bought the kit years ago and never got to building it. The barrel was made by Bill and is 20 gauge, 8" long, and stamped with correct London proof marks and "WK" . I show it against a barrel from a long land Brown Bess. The precarved stock is English walnut and the hardware was cast by Bill in brass and is superb. The lock is Chambers small round-faced English lock, which is a very fine lock with a little work. It uses small Siler internals. I show it against an early Brown Bess lock for comparison.

So for me, the first question is, what am I going to make? What will the pistol represent? Unlike many, I care a lot about historical consistency. So I had to figure out what I had to work with. The pistol is mostly consistent with moderate quality pistols from the era. For example, it has the classic British acorn trigger guard. That became popular during the 1770s but by then, high quality pistols would have flat-faced locks. The round-faced lock was relegated to military, livery, and trade guns by that time. If the trigger guard was of an earlier style such that the pistol could credibly be from the 1750s, I could create a high-end gun. As it is, it needs to represent a less expensive gun from the 1770s and a private purchase officer's side arm is the historical ticket. So that is what it will be. It will represent a modest quality pistol purchased by an officer without the wealth to buy a higher grade. So what does that mean? It means I build it as is, I include a little carving around the barrel tang, and the engraving will be effective but not highest quality. There won't be a hook and tang breech nor high-end ribbed ramrod pipes and silver wire inlay. It will have the facade of quality without the details. Now at that time, that meant a very well made gun compared to American colonial production but without the frills associated with first quality London production.

So here I go on another historical adventure. The first issue to resolve is the breech plug threads go really deep into the barrel. So deep, that there is no way I could position the lock in the precarved mortice to avoid the touch hole going right in to the breech plug. I did not want to move the barrel back because I want the fence of the lock to be correctly located at the end of the barrel. The solution was to hollow out the breech plug and notch it for the lock. It is really simple to do with drills and a drill press, and then grinders attached to a Dremel. It came out nicely and solves the problem. I will inlet the barrel tomorrow, so more is coming.

dave