SgtErv,

As to Barrel or Muzzle “coning,” I think you may be mistaking terminology. Don’t feel bad, though, because even today people often use incorrect terminology and that includes people in the gunsmithing trade. To better explain it, I think we should go over how the muzzle end of the rifle or gun barrels were finished in the period and now.

So we are all on the same page, I would like to use the common term for the end of the barrel as the “Barrel Face.” We now know that if the face is not uniform to the bore, no matter the shape of the face, the gas coming out of the bore will drive the bullet away from the line of the bore and “throw the bullet off” just as it exists the muzzle. There is no doubt in my mind that they realized this in the period even if they did not understand all the science behind it. The common shape of the face of the few 18th century rifles I have seen and most early 19th century rifles was flat. This was fairly easy to do when they went from swamped barrels to straight barrels because with a straight barrel, you can place a Square along the barrel flats to see if the barrel face is perpendicular to the sides. However, with a swamped barrel where the barrel flats are not uniform OR on a tapered round barrel, you really can’t use a Square. OK, so how did they ensure the muzzle face was uniform to the bore?

One might suggest they put a barrel in a lathe between live centers to use a cutting tool to face the end of the barrel. Rudimentary versions of such lathes did exist in the 18th century, but the length and weight of rifle barrels AND the fact the swamped sides of the barrel were not parallel, all would have made this extremely difficult if not improbable or even impossible. So how did they do it in the 18th century? Well, since I have done this work by hand on modern barrels and some muzzle loaders, the easiest way for them to have done it would be to make a piloted cutter where the cutter’s pilot just fit into the bore. So, did they have a piloted cutter like that in the 18th century? The answer is a resounding YES.

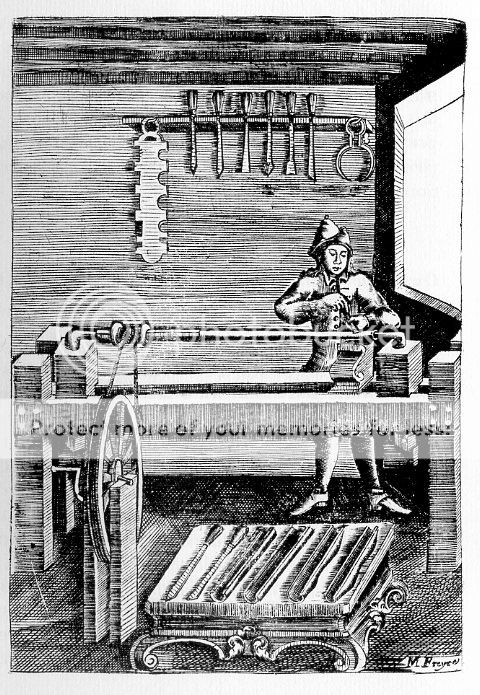

Denis Diderot edited/published a “Encyclopaedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts” with one engraved plate on a gunsmith’s work that is germane to this discussion. Please see the tools listed below in the linked engraved plate.

Figure 33 appears to be a cone shaped tool for “crowning” or “chamfering” the bore at the muzzle

Figure 32 (to the immediate right of Figure 33) appears to be a Muzzle Facing Tool or at least a piloted cutter to cut a flat face that is perpendicular to a bored hole

BTW, you can click on the link and it will enlarge to see the individual tools better.

http://artflx.uchicago.edu/images/encyclopedie/V18/plate_18_9_4.jpeg

OK, so a tool such as “Figure 32” would cut the barrel face perpendicular to the bore in the barrel. That left a sharp edge all around the outer edge of the bore that could/would catch on or shave the ball during loading or cut the patch. To get rid of that sharp edge, a tool such as Figure 33 would be used to lightly chamfer/crown the bore at the muzzle. That put an angled surface all around the bore at the Barrel Face. This chamfering/crowing is not “coning,” as coning actually cuts down further into the bore. However, some folks have mistakenly used the term “coning” for what was actually Barrel Crowning/Chamfering

There was also another type of Bore Chamfering that was done at times in the 18th century. Instead of a tool like Figure 33, this was done with small files and probably very carefully by hand. The grooves of the bore were filed at the muzzle so there was a rounded edge on them and deeper than the lesser amount of rounding that was done on the lands. This also acted to allow the patch material to “ease” into the bore, as the patch material was squeezed into the grooves, instead of having to compress in a very short distance of the bore from the muzzle.

Gus

..something in Polish I think.....a member here owns one...

..something in Polish I think.....a member here owns one... ..something in Polish I think.....a member here owns one...

..something in Polish I think.....a member here owns one...